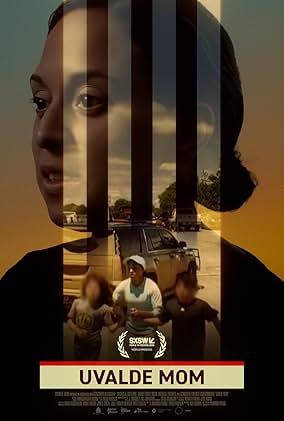

“Uvalde Mom” (2025) refers to Angeli Rose Gomez, a mom of two boys who exercised her human right to be civilly disobedient on May 24, 2022. Gomez entered Robb Elementary School in Uvalde Texas, was familiar with the grounds because she went to school there and saved her children and another relative while an active shooter killed teachers and students. The documentary focuses on the history of the community, the events and aftermath of that mass shooting and the state government and law enforcement role in the community. Cowriter and director Anayansi Prado’s documentary should be required viewing for every American.

The protagonist of “Uvalde Mom” is Gomez, a tiny woman who does not want to be called a hero but clearly meets the definition of the word. Before offering details about Gomez’s historic rescue, Prado prefers to introduce Gomez in the same way that she lives her life: getting her kids ready for school. She was not the only parent who tried to rescue their kids, but she is the only one who succeeded. Prado rewinds to include Gomez’s life story prior to that fateful day. Gomez is no angel, and thank God because without her flaws (or her leadership skills if her demographic profile was different), she would not have succeeded when it counts. She went from being an athlete and grade A student to a woman on probation because in 2014, she hit her sons’ father with a car when he tried to kidnap one of them.

“Uvalde Mom” sticks to the human element of this story and is not a preach to the choir documentary. In other words, different people may draw different conclusions while watching the same film. Texas is a stand your ground state, yet that law was not applied in her 2014 case. According to interviews conducted exclusively for the documentary, she was convicted with 6 felonies which resulted in six months of prison and five years of probation. It was not the point of this story to delve into the legal details regarding whether this punishment was warranted considering the circumstances. Criminal law is supposed to prevent action that harms the community, and while ideally, citizens should not hit people with their car, considering that people were begging for that right against protestors in traffic, especially since her partner did not get punished for repeatedly hurting her, the favor should be returned since it seemed to be her first and only act of reactive abuse, which is a thing. If someone is only violent after repeated abuse, it does not make that person endemically abusive. It is a fancy psychological term for self-defense. Because she learned that the cops did not intervene in domestic violence, she took matters into her own hands then and on the day of the shooting. Both times, she was met with more government reprisals than the other guy.

Gomez’s story becomes a microcosm of what conduct is acceptable to the government. Prado uses a ton of montages including television news coverage, newspaper and magazine headlines, recorded government meetings with citizens speaking up (literally the school council is on the stage, and the public is positioned below them) to show the ensuing tug of war between the public and the government which is supposed to represent them. These clips include Gomez speaking out against law enforcement’s inaction, which was not just anecdotal, but verified when the government released footage showing law enforcement standing around a hall in defensive posture. “Uvalde Mom” includes this footage. The implication is that the government cares more about looking foolish in the media and other people becoming vigilantes than doing their job. They use the fear of arrest and physical force against unarmed law-abiding citizens to squelch the natural impulse to protect their children.

Gomez’s story also becomes one of unreasonable extended and constant surveillance of a citizen because of criminal history, which can be weaponized if a person angers the right person in government. “Uvalde Mom” does not go into the logistics of why her probation seemed to extend long before the crime committed, but an educated guess could be the delay in sentencing. This monitoring means any action, perceived or actual, rises to the level of a criminal violation. Her criminal defense attorney, Shannon Locke, stated that the allegations were that she did not report for meetings, left the county without written permission and used THC. Later, unsubstantiated allegations of photographs showing her drinking alcohol was sufficient to incarcerate her again.

Without condoning any of these acts, the implication is that beating your romantic partner is something that law enforcement is powerless to act on but drinking, using recreational marijuana and defending and rescuing a kid from a parent breaking into a home in the middle of the night and taking the kid require swift reprisals. Buying a gun between eighteen and twenty-one is not only legal, but a right that needs to be protected even with the benefit of hindsight. It does not matter if the legal appropriate process is pursued and succeeds in the state house to use gun control. It is also legal to not follow the legislative rules and ignore the people’s wishes. The film winds down on a terrifying note that law enforcement may have set its sights on one of Gomez’s sons too when he considers carrying an aerosol gun to defend himself if another shooter arrives while his mom is incarcerated. The logic that tracks in these laws are the state mandated disapproval of the vulnerable defending or soothing themselves under stressful circumstances and people exercising offensive force, which may explain the subconscious refusal of law enforcement to confront the shooter besides fear. Marie Miller, a lawyer from the Institute of Justice, is the only talking head who analyzes the situation and offers other conclusions. Otherwise, this documentary is told through the eyes of the community, especially people who know Gomez.

Prado interviews Arnulfo Reyes, a teacher who survived the shooting, Lavonne De Leon, Gomez’s mom, John Gatica, Gomez’s principal when she was a child, to discuss their perspective on Gomez’s actions and the reactions to it. Gomez’s mom and Gomez have two heart-to-heart talks in the car with De Leon driving and Gomez in the back seat. Gomez gets few casual moments with friends, but a casual supportive encounter with Melanyi J. Moreno, owner of Melanyi’s Makeup and More Store, and Gomez’s cousin, Rhianncé, government name Isaac Sanchez, who cross-dresses. These moments are like a glass of water in a desert because of the intensity of Gomez’s life. Gomez’s grandmother stays silent though appears on screen, and it was intriguing that she is only pictured with Gomez, not De Leon.

“Uvalde Mom” rewinds briefly to show the history of the school and how race and class divide the town and its resources. In 1970, there was a six week walk out at the school because the town did not renew the contract of the only Mexican teacher. Tina Quintanilla, PhD, Gomez’s friend who also has a daughter, explains the town dynamic in interviews for the documentary. Most of the community usually keeps their mouth shut to avoid financial repercussions. While there may not be a well thought out conspiracy against anyone, systemic is another way to describe the gravity that rules the town’s knee jerk reaction to someone like Gomez, who wanted to be a cop, was the granddaughter of the first Hispanic chief of police and was a star student. If Gomez could be swiftly criminalized instead of rehabilitated despite her pedigree, accomplishments and bright future, who else could be. In other words, unconscious bias exists. In another world, maybe with more money, she could be the Secretary of Health and Human Services, but she also falls short because when she hurts people, it is to save children.

Have tissues within reach when watching “Uvalde Mom.” It is a terrifying story, but not because of the mass murder. People are being punished for having natural human instincts and groomed to accept unnatural behavior such as criminalizing protecting their children to prioritize political values, not people, and heed authority regardless of whether that authority is acting lawfully. Gomez’s heroism is the only reason that anyone outside of Uvalde are aware of the unjust power dynamics. Gomez saved her kids two separate times, and law enforcement did not. Prado tells a story that goes beyond hagiography and the headlines but is a rigorous, incisive, unflinching story that tells the story of a town and a state that also reflects a larger American story.