The Darren Aronofsky film that you do not want to miss isn’t “Caught Stealing” (2025), but “Sabbath Queen” (2024), a documentary which Aronofsky served as executive producer. This film is about Amichal Lau-Lavie, an Israeli who came to Manhattan after a journalist outted him without his consent because he belonged to a high profile family. Lau-Lavie is known for balancing tradition while carving a new way to continue the family business of worshipping God and serving his community as the thirty-ninth consecutive generation of rabbis, which amounts to 1000 years. Director Sandi Simcha DuBowski embeds with Lau-Lavie for twenty-one years in this participatory documentary. Not attention seeking, Lau-Lavie is occasionally uncomfortable with answering DuBowski’s questions on camera because of the self-imposed pressure of being authentic, living up to a high standard and creating something counter cultural.

I am not Jewish, but as a person interested in deconstructing fundamentalist lessons in faith taught in childhood, Lau-Lavie’s life is relatable as a man in exile from a world that used to be home, but he does not belong to because of who he is. The film is thematic, cyclical, and nonchronological without confusing viewers. The overall story is framed using the “how we got here” approach or in medias res on the precipice of another impending exile when Lau-Lavie prepares to perform an interfaith, same sex marriage, which means breaking conservative rabbinical law (civil disobedience). It is only a part of a cycle of following God and seeing the definition of Jewish as broader than defined in orthodox or conservative circles.

Lau-Lavie and DuBowski are wedded to providing context as the foundation of the film and Lau-Lavie’s life. It is more about integrating and interweaving the past with the present instead of a disaffected, angry separation and disavowal of the past. Lau-Lavie is treated as another chapter, not a new book, in his family history though DuBowski’s audible questions and the family’s answers suggest that others may disagree. The animation shows how far back in time Lau-Lavie’s line goes back. Lau-Lavie is often the de facto narrator of most of the film. His reflections even accompany the black and white archival footage of Poland used during the sequence when his father returns with his sons at a point in “Sabbath Queen” when a more academic film would segue to a historian dropping facts to the audience. In contrast, DuBowski treats Lau-Lavie as the voice of authority based on his personal experience as a descendent of those who survived the Holocaust and seeks to keep the promise of continuing to minister to his congregation even in the direst of circumstance, which thankfully has not risen to that level of horror, but translates into often exposing himself to a civil war level of vitriol as he wears his family history like armor while protesting or anticipating ejection from another group.

DuBowski does not pull punches and compiles archival clips of people, including Lau-Lavie’s high-profile relatives, talking about how orthodox Jewish people see progressive Jewish people and conducts exclusive interviews with Lau-Lavie’s also famous brother, Rabbi Benny Lau, and Joan Lau, their mother. “Sabbath Queen” toggles between Jerusalem and Manhattan in an Abrahamic way of choosing an unknown path and leaving the land of your father to follow God and embrace, instead of annihilating, himself. It is a journey that he is familiar with since earlier, he expressed empathy over Jewish women not being able to pray in a certain location because of their gender then went to the desert before having to flee further to New York. That empathy solidifies when Lau-Lavie in drag has a tete a tete with Alice Shakvi, an Israeli feminist, about the Shechinah, feminine energy and divine. The illustration in the opening sequence, which is repeated later in the documentary, is a response to a need to release the titular character as a side of God that got rejected. In many ways, the documentary is an extension of that release of animating energy that propels and fuels Lau-Lavie to do the work in another land.

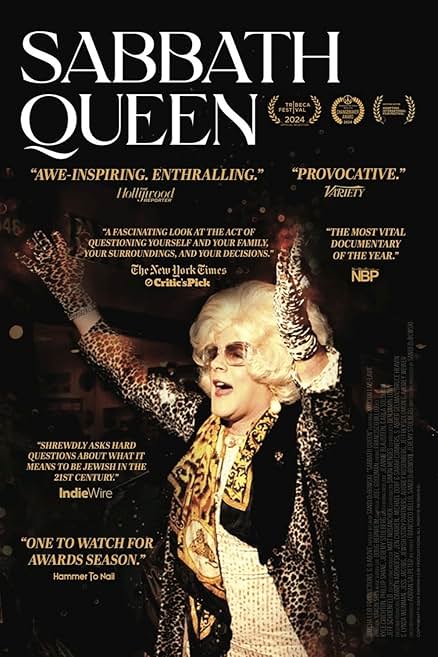

Anyone familiar with New York in the Nineties will feel at home with the compilation of home video excerpts that depict Lau-Lavie’s entry into the queer world as a gay man and his circuitous journey back to following the calling to become a leader in his faith. It is a nontraditional journey from celebrating club culture, joining the Radical Faeries, performing in drag as Rebbetzin Hadassah Gross or as an artist (instead of a rabbi) in the theatrical Storahtelling to retell Torah stories for a contemporary audience, then presiding at a God-optional synagogue Lab/Shul that practices Judaism in an ecumenical environment. The excerpts of these performances and/or ceremonies are quite moving and reflect how many people yearn to have a community that adheres to the way that Lau-Lavie lives: not rejecting their heritage or God but rejecting the notion that there is only one way to embody it. If the number of Jewish people are decreasing, “Sabbath Queen” implies that it is not from lack of desire, but expulsion for not conforming.

Lau-Lavie finally lands at studying at the Jewish Theological Seminary to become a conservative rabbi. Though less stringent than Lau-Lavie’s family, the conservative movement still has nonnegotiable rules. Rabbi Daniel S. Nevins offers an interview to show how open they are, and there are images of Lau-Lavie’s life on campus such as classrooms and study groups. As he gets older, Lau-Lavie is still performing in a different kind of drag, conservative camouflage. One rule is no interfaith marriage, which means that he can no longer officiate weddings and may not even be present for one. The most riveting scene unfolds at Lab/Shul board meeting at a restaurant, City Winery. An unnamed board memory declares, “I don’t want to lose you.” The tension is that Lau-Lavie wants weapons to fight orthodoxy theologically, but he is fighting to belong when he already does just not where he wants to, with his family. If “Sabbath Queen” had not begun with the ending, there would be some genuine tension that Lau-Lavie was changing course and self-abandoning.

“Sabbath Queen” is about Lau-Lavie’s grief over his father, upholding family tradition, address unresolved lack of acceptance and looking for external legitimacy and authority as if his current innate existence is insufficient. He still cares about earning the establishment’s respect, but if he receives it, those who gave it would lose their status of establishment and become outsiders like him. Lab/Shul cofounder Shira Kline offers an interview that teases out her frustration with her friend’s choice, especially since she shares a similar background. Though not explicit, this part of his story is the male part and universal. Who does not dream of fitting in? The Lau-Lavie clan does respect his title as rabbi even if it is not from an orthodox institution. They travel from Israel for his graduation, which is not shown previously, which includes staying home for family member milestones. While he stays mum about his current relationship status, he is frank about being a sperm donor and an active father, another way to continue the family line, but the family just enjoy their newest members virtually via radio.

Earlier in “Sabbath Queen,” the documentary shows what he is giving up. Interviews with interfaith couples such as Jai and Elana, a Hindu and Jewish couple, Zahra and Nat, a Muslim and Jewish couple, are juxtaposed with the wedding day and footage of prominent talking heads in the Jewish community denouncing such marriages. The documentary wins because real, visible happy faces always beat theoretical pitch perfect, but loveless adherence to the law. A poignant montage of photos of Lau-Lavai and his most impactful romantic relationship is with a Catholic man who also shared a calling to ministry, which says more about their similarities and compatibility than difference. It is not like the strict people have a program where they can guarantee the perfect Jewish mate. Co-founders of NY Zen Center, Sensei Koshin Paley Ellison and Sensei Chodo Campbell, two self-proclaimed JewBoos (Jewish Buddhists), offer the incentive to shake what his grad school studying gave him: to argue for interfaith marriage using the term Ger Toshav, neither Jewish, nor Gentile, but a person who is part of the Jewish community. In other words, rabbis are lawyers and historians, but the judge is also the person that he is arguing against, so the game is rigged. A montage of news headlines, including from Jane Eisner, journalist and editor of The Forward, who appears briefly in the film, reveal that reason, not tradition, is a thing of the past.

DuBowski’s decision to root “Sabbath Queen” in the story of a very unusual, historic family is brilliant. The specificity of Lau-Lavie’s life makes this story relatable either to people who see him as the prodigal son who won’t fit in but is still loved or as the person who refuses to let go of his community until they bless him and anyone else whom God loves. There are some who will see his good intentions as a threat, but they are not the audience. This struggle for the right to be with God and be seen as such is such a strange struggle as if any human being can stop God from interacting with those whom we disapprove of.