“Folktales” (2025) is a poetic, coming of age documentary about a year at Pasvik Folk High School in Finnmark, Norway, which is close to the Russian border and is 200 miles above the Arctic Circle. Based on how it is presented in the film, it offers students a year of independence between ending school as a child and becoming an adult. The goal is to create a curriculum that speaks to the human brain which is experiencing a 10,000-year lag before it can evolve to this time. The curriculum’s focal point is for students to be responsible for taking care of sledding dogs. Will these students find happiness?

Normally I wait until after I finish watching a film to get any information about it so I can replicate the experience that most people bring when going to the movies. When I watched “Folktales” (2025), I thought, “This reminds me of ‘Jesus Camp’ (2006),” and after I finished watching it, bam, I discovered that Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady directed both films though it felt as if the codirectors admired the Norwegian experience more and thought it worked whereas the earlier movie is like watching a horror film. Though these folk schools are secular, the filmmakers use Norse mythology as a narrative device to describe the human quest to find happiness, specifically the tale of Odin going to the Norns to ask for the gift of happiness, which they refuse to give because everyone must discover it for themselves. You may be familiar with the Norns if you watched “The Northman” (2022). The film uses imagery of red yarn and knitting to symbolize the fate of a person’s life.

“Folktales” follows three young adults: nineteen-year-old Hege Wik from Sandnes, Norway, nineteen-year-old Bjorn Tore Maseld from Fauske, Norway, and eighteen-year-old Romain Biannic from Groningen, Netherlands. Each student shares the underlying reason why they decided to enter this program. “Folktales” shows that change does not happen overnight, and they flounder at engaging in unfamiliar tasks that involve the rugged outdoors and living beings dependent on them. Some take longer than others to find their way, and they find a foothold in different ways. The film mostly restricts itself to showing the young people’s interactions with the dogs, the outdoors and instructors, not the other activities or time with students who are not being profiled in the documentary.

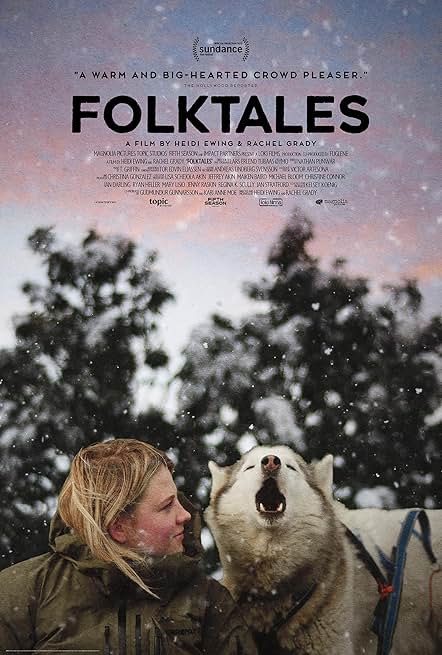

Because it is a poetic documentary, “Folktales” is less about comprehensively showing how or if the program works but offers snapshots of how it feels. Like “Final Vows” (2024), the filmmakers may be trying to replicate the experience for the viewers, not document logistics, but it may not be as effective in conveying it to viewers. There are a plethora of montages involving the expansive wilderness that is untouched compared to their earlier lives. It is an argument for seeing it on the big screen so you can focus on the majesty in an appropriate form without any distractions. Watching it at home on a smaller screen makes it more difficult to concentrate on the deliberate pacing and transcendent imagery. Also, there are dogs, and while the program consists of more than just hugging them, it seems like a huge part of the program consists of the healing power of just being around adorable, indomitable fluffy puppers, which is an undeniable draw.

Instead of a narrator, context was written onscreen, and usually clustered, which was incredibly helpful. When the documentary participants initially appear on screen, their name and title or background information was printed soon thereafter. Some of the dogs were introduced, but did not get the same courtesy, which may seem like a silly quibble, but these dogs are the cornerstone of this program and should be awarded the same respect as any of the participants. Only three were named though more lived there. The instructors stress how important it is for the students to get to know them, and “Folktales” should have mirrored that sensibility within the narrative structure to truly replicate the experience. There is one dog who is getting hugged so much and looks at the camera as if to say, “Um, I love this person, but I also have things to do today. Can you help me get out of here?”

The profiled instructors are Ketil, the principal who is shown giving an orienting speech to the incoming class; Iselin, a dog sledding teacher who offered the aforementioned neurological tip about brain evolution; and Thor-Atle, another dog sledding teacher who introduces the dogs to the students and the audience. The teachers are often depicted as they are talking with the students, but occasionally they talk amongst themselves about their pupils, and they still have that sense of irrepressible energy that in the US, only relatively new teachers have. They are clearly true believers in the program, are eager to impart their knowledge, have faith in their students ability to adapt and excel even in a physically hostile environment and give their students tools to autonomy, not indoctrination, though as an American watching, it is hard to keep the innate cynicism at bay and wonder what the real agenda is.

“Folktales” is disinterested in proving that the program works but answers the question of whether the students are happier in Finnmark or at their respective homes. Only Wik’s life before and after arriving at Finnmark is shown. Maseld and Biannic only offer anecdotes that give glimpses of their lives outside Finnmark. If Maseld was still a child, the entire world may try to adopt him because he arrives with the incorrect belief that he is “nice but annoying.” Dear reader, many young men are annoying, but Maseld is not one of them, and I hope that I speak for everyone who would like to just talk to the people who feel that way for a few seconds. Eventually he blossoms, and Biannic’s impression of him is that Maseld is fearless, authentic and does not care what other people think when the opposite is the truth. Biannic mostly discusses his interior life without clues regarding whether any external factors contributed to his self-professed negative mindset. They all seem like really normal, sweet young ones trying to find their footsteps.

The instructors claimed correctly that kids like Biannic came from all over the world, and it would have been interesting if “Folktales” showed that adjustment. One Spanish speaking student remarked that there is no “ethnic” presence. Though understandable because of limited time, it was disappointing to get teasers about the other students and not have any follow up. There are other aspects of the program, but the film only devotes a brief amount of time to it.

As an American unfamiliar with the concept of a folk school, the title threw me off because folk tales are associated with mythology, which is not central to this movie. It is silly, but if a title is too cumbersome or is not easily associated with the subject matter, it may be enough of a barrier for the right audience to know about this film. “Folktales” is perfect for a niche audience interested in childhood development and alternative education or just learning about Norwegian culture. It is not for everyone since it also has subtitles and does not follow the narrative beats of the average documentary.