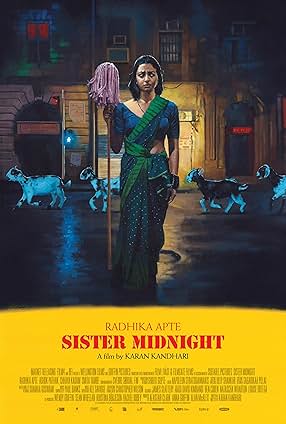

“Sister Midnight” (2024) follows newlywed Uma (Radhika Apte) as she adjusts to life in Mumbai with her husband, Gopal (Ashok Pathak). It turns out that neither of them is prepared for married life. Frustrated at how small her world feels and her limitations, Uma’s acerbic way of interacting with the world includes chastising clouds for hiding the moon. So, when she begins to act in an unusual manner, even for her, she is at a loss about how to navigate it. Will any place or person feels like home? Can she be comfortable in her own skin?

The less that you know about “Sister Midnight” before seeing it, the better. It is a fresh, funny, surprising film that benefits from the cultural divide. If you come to the movie like a blank slate, you will instantly relate to Uma, an angry fish out of water who does not give the impression of a woman who has ever done what was expected, somehow still got married and is pissed that life as a wife does not measure up to whatever she imagined.

“Sister Midnight” rests on Apte’s shoulders. It is impossible to imagine anyone else in this part. Her physicality, kinetic energy, dead pan, sharp tongued delivery and sensuous impulses are a mélange of traits counterintuitive in a stay-at-home bride from an arranged marriage. Apte’s restless, dissatisfied character understands what her duties are, but she does not have the skill or demeanor to pull it off. It is as if no one socialized her as a girl regarding how she is supposed to exist in the world, but she got enough of the programming to take the first steps into that life. She roams around, wants to play, follows her impulses and expresses dissatisfaction. When she tries to engage in housework, it is like putting a leash on a cat. You can do it, but it looks funny, and everyone knows that if the cat goes along with it, the cat is humoring you, but it is not normal.

Eagle-eyed viewers retroactively reflecting and scrutinizing “Sister Midnight” will recognize when Uma reaches a point when her future changes course. Who says silent film is dead? For the first part of the film, neither Uma nor Gopal talk, but Uma uses her body language, specifically her green bangles, to express herself. It is not explicitly stated, but the couple seem to be Marathis, who are originally from the coast and mostly consists of Hindu people, i.e. vegetarians. When the bangles’ movement and noise do not reflect how she feels, she holds her arms stiffly to refrain from discourse. Green bangles symbolize health for the women, fertility within the marriage and safety for the husband. It also is supposed to be a symbol for the individual and collective wealth of the couple, but that ship has sailed considering the couple’s one room home puts them in constant, uncomfortable proximity to each other and their neighbors. Even a happy couple would find such accommodations challenging. She asks someone to break the bangles and writer/director Karan Kandhari in his sophomore feature film cuts to black. The second moment is when the couple go to Gopal’s cousin’s wedding, and Uma acts on her annoyance over the diegetic disturbing sound of a nearby bug zapper much to the audible disapproval of the fellow guests, but to the delight of an opportunistic mosquito who seizes on the opportunity of lowered defenses. At the end, on a train, there will be a close up shot that reveals that Uma is not delusional, and she has changed forever.

The rest of “Sister Midnight” is a gonzo ride that at first seems normal. Gopal is frequently sick so when it is Uma’s turn, it does not immediately raise an alarm. Then everyone compliments Uma for her complexion and asks for the secret of her beauty regimen, a casual nod to the universal plague of colorism. For viewers who do not get how Uma transformed, Kandhari stops being subtle and raises the stakes with some stop motion animals that work because of the incessant humor injected into the horrors of the confining nature of adult life as a married person. Kandhari is less concerned about the exponential implications of Uma’s condition though depicted because then the tone of the movie would shift to apocalyptic. It may be a nagging flaw in the narrative’s logic, but it is about Uma’s interior life, not the fate of the world, which keeps on strumming like normal.

Kandhari’s “Sister Midnight” is focused on Uma, but her surrounding community seems real whether it is an oblivious guy trying to throw out his garbage or Gopal’s ineptitude which grows into acceptance and concern. Uma’s next-door neighbor, reluctant teacher and friend, Sheetal (Chhaya Kadam), gives her blunt lessons on the inane eternity of cooking meals and maintaining a house while Sheetal also adores her husband and physically dominates any space that she is in. When people talk about traditional women, these sandpaper tongued, blunt force interactions are not what they imagine.

“Sister Midnight” has been compared to Wes Anderson’s films, but Kandhari and editor Napoleon Stratogiannakis style does not require any dialogue. They have a way of making a small room feel miniscule or expansive. The cuts contain all the necessary content. The most obvious example is a series of panning shots which alternate between Gopal and Uma walking home in the day with the camera following each of them from left to right parallel to the one room houses which show normal vignettes of family life: the women keeping house, then the women serving the men; thus giving us a snapshot of typical life contrasted with the main couple. In one of the last reprises of this shot, Gopal arrives home, but the camera continues by following Uma who leaves for work at the same time as her husband’s arrival. Their relationship is almost nonexistent since they no longer attempt to share the same space, yet their story becomes a plausible, tender love story.

“Sister Midnight” does not stop there. A person does not find fulfillment in relationships so even with good friendships, including Hijra people (third gender), a caring coworker and a loving husband, Uma must make peace with herself and choosing to live in a world where she will probably never know peace. If the resolution does not feel satisfying, it is not supposed to. Just because Uma accepts herself and recognizes that she does not fit, it does not mean that she will stop feeling exasperated about her situation or get to exist without someone injecting themselves into her business. Until Kandhari has reached the end of his life, he won’t know or be able to write about whether it is possible to achieve that level of comfort in existing in a world not meant for anyone.

This existential crisis reaches the zenith of hilarity when Uma jumps on a train to reach the coast then looks at either side of her and witnesses others sobbing. Instead of surrendering to the morass of emotions, she acts, moves, lashes out and sleeps. “Sister Midnight” has an alluring energy even if it is not one that should be emulated. She may be on a train to nowhere, but at least Uma is an unedited, undiluted version of herself who lives fully.