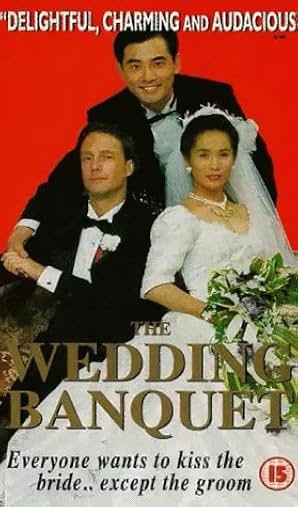

You’re going to need to put some respect on Ang Lee’s “The Wedding Banquet” (1993) before going gaga over films like “On Swift Horses” (2024) and the 2025 remake “The Wedding Banquet.” I felt the need to revisit the classic and devote more analysis of it than I did when I was still new to the reviewing business and prioritizing my visceral reactions as a viewer than text analysis. These later films are as deep as kiddie pool when it comes to authentic emotions, relationship dynamics, culture, family, immigration and sexuality. Taiwanese immigrant and Manhattan businessman Wai-Tung Gao (Winston Chao) is in a loving committed relationship with American physical therapist Simon (Mitchell Lichtenstein), but the Gao family do not know that Wai-Tung is gay. They keep hiring matchmakers to find the right woman. When they decide to visit, Simon has the brilliant idea of pretending that Wei-Tung’s tenant, Wei-Wei (May Chin), who has an open crush on her landlord, is his fiancé. Without a job and about to be deported, Wei-Wei jumps at the chance for some stability, financial security and community. As Robert Burns write, “the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry.”

“The Wedding Banquet” is based on a real story that co-writer Neil Peng got from a friend—the premise. It explains why the film feels so grounded in a way that the remake does not. Everyone has heat with each other and is sexy. Chao and Chin are smoke shows. From the first time that Wei-Wei appears, she is alone and drenched literally and figuratively. She is alluring for no good reason. Even before the parents arrive, Wai-Tung and Wei-Wei’s relationship is not professional. He cares about her as a fellow immigrant despite their socioeconomic differences, but he also takes his precious time snapping out of her seductive playfulness. His relationship with Simon is passionate, but they have been a de facto married couple whereas Wei-Wei is the other woman, but Simon does not initially have an issue with it even when she plays in his face. Lichtenstein resembles Andrew McCarthy, and the problem with being in such a hot cast is looking comparatively plain, but Simon is such a sweetie pie who does his best to find a place in the family, and he holds a special place as the one who does no wrong and is so earnest. Ah-Lei Gua and Sihung Lung, who respectively play Mrs. and Mr. Gao’s entrance, deliver a breathtaking, powerful first impression when they appear at the airport. “On Swift Horses” is hot if you live in Antarctica and are looking at physical attraction through a strobe light and revolving doors, fractions of experience as opposed to a whole picture.

Even as “The Wedding Banquet” takes it characters on a winding journey, the narrative structure is clean and flows smoothly. The first part establishes the main characters’ routine and dynamic in America. It is Western, money-oriented and fleeting. From the opening scene, Lee pairs Mrs. Gao’s voice with the sound of heavy equipment clashing at the gym—a river and steel. While Wai-Tung describes his family as a burden, they humanize him. Simon anchors Wai-Tung’s three-dimensional world so he does not continuously prioritize earning money. The second part is the culture clash between Western and Eastern ways. Only Simon is the kin keeper and teaches Wei-Wei how to take his place. Wai-Tung treats his family like an appointment, but he is not a monster just dealing with a jumble of issues from hiding his identity. When the family (the Gaos, Simon and Wei-Wei) enter a Chinese space, a Chinese restaurant, the story shifts into bringing home back to the two immigrants. Most of the characters are immigrants. The Gaos immigrated from mainland China to Taiwan. Though both are Chinese, Wei-Wei and Wai-Tung immigrated from different countries, Taiwan and Shanghai respectively. The title refers to a celebration where everyone enters a liminal, temporal space of being back home. The white characters, including Simon, are more like extras than supporting characters. The third part is the resettling of the seismic shift in everyone’s relationship because of the strain of living a lie. Simon is rightfully tired of pretending not to matter. Wei-Wei feels as if she is lying to people that she loves. Wai-Tung is letting everyone down because he does not love Wei-Wei despite external appearances, and he loves Simon but is betraying him. The final act is about finding the balance between honoring the father and themselves.

“The Wedding Banquet” is a story about love, anticipated grief and the legacy of World War II. Everyone loves Mr. Gao. He is a Chinese Army war hero who then had to flee to Taiwan. He enlists to avoid an arranged marriage for unknown reasons (was he gay?), but during World War II, his entire family dies. Y’all, read between the lines. They did not just die like Camille on a fainting couch. The Japanese probably brutally murdered them. So then he marries to keep his family alive so having babies is not just this selfish impulse of wanting a kid like a small dog that you put in your purse but do not see as a real person. It is an act of defiance and survival. Then Mrs. Gao confides to Wei-Wei that she could only have one child, and Wai-Tung was a weakly child. So those opening scenes at the gym is another triumph. In Western culture, people neuter Asian men, but a defiant media image is a strong Chinese man as another rebuke to World War II and Western standards. Then this Chinese man has taken an American de facto spouse, another image of defiance when movies would hint at Asian and white characters’ attraction to each other, but not consummate it. So having a kid becomes an act of rebellion. The Gaos are not full of themselves and think that they have a standard to live up to. They want to exist because they were nearly exterminated. That wedding banquet is about defiant joy with their host, Old Chen (Tien Pien), a witness to that time and honoring Gao’s heroism in war and life.

There is an early scene before the Gaos arrive when Wai-Tung discovers that his dad is sick, but his mother never told him. While of course there is the Damocles sword of homophobia if his parents discover the truth, Wai-Tung does everything to make his dad happy before he dies: the wife, the banquet, the baby. The most poignant scene is when he sees his father sleeping on armchair and is concerned that Mr. Gao has died. Wai-Tung is feeling the mortality of his loved one, which complicates his feelings of guilt towards his partner and wife. “The Wedding Banquet” nails this feeling of anticipated, inevitable grief which dominates the end of the narrative. Simon only expresses ire at Wai-Tung for not using protection and is shown outdoors canvassing with a banner that says “Silence=Death,” AIDS activism. Even though it is the twenty-first century, that pandemic was still unfolding in Indiana.

It is also a film about money. Even though Wai-Tung seems relatively well-off, he is very conscience at how quickly everything can go to crap. He is a workaholic because he does not believe that financial success is a given. He is essentially a slumlord, does the repairs himself and does the literal heavy lifting. He shares an office with his employees.

It is these little details that could go unnoticed that make “The Wedding Banquet” into not just another awkward love triangle under farcical circumstances, but a dramedy that lives and breathes in the real world. It also takes place in New York when it still had grit and was broken down. It is more textured and three-dimensional than its successors.