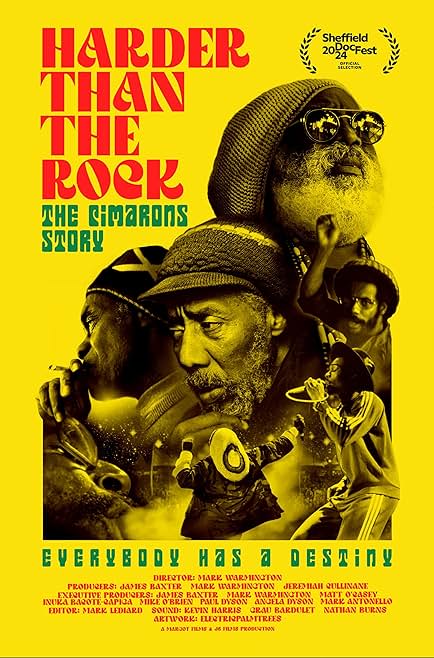

“Harder than the Rock: The Cimarons Story” is a documentary about the Jamaican British reggae band, the Cimarons, who predate Bob Marley’s arrival in Europe, spanning from their start in Harlesden to their most recent performance in Spain in August 2023. While the composition of the band may change, their music never has. Cinematographer Mark Warmington in his directorial debut creates a deep cut movie, but for those unfamiliar with the band, newcomers could flounder a bit while appreciating the music, vibes and aesthetic.

My kingdom for a cohesive narrative. “Harder than the Rock” is really two documentaries in one, and it was possible to make an engrossing, textured story to bring in the newbies. The first half is more of a basic, paint by numbers summary of The Cimarons biography as a band which amounts to a list with colorful archival footage from performances or tight close ups of musical instruments and equipment. Warmington waits too long to differentiate and identify the talking heads and the band members then when he does, he does not spend enough time individuating them, which means it is challenging to differentiate anyone, which is crucial to the second half of the film. David Katz is an author who opines about their fame. What did he write that makes him an expert? Dunno. Academic Mykaell Riley is also associated with Steel Pulse, a reggae band, so his commentary seems grounded, especially since he discusses his expertise as if it is grounded in first-hand experience. He offers the most context when describing the neighborhood and why it would be a magnet for great Caribbean music. General Levy, an English DJ, is an admirer, and he probably exists to attract potential younger viewers who admire him and would watch the documentary for him then accidentally learn about the UK band. Diane White, a reggae musician, is another admirer and seems to exist so that the film is not a sausage fest. She does not get a lot of screen time.

The Cimarons’ individual function defines them: what instrument they play, how long they were in the band, etc. Locksley Giche plays the guitar, and Franklyn Dunn is on bass. Giche and Dunn are the founding members. Carl Levy is on the “keys,” organ or keyboards. The vocalists change and not everyone appears on screen: Carl Bert, Bobby ‘Dego’ Davis, Winston Reedy and newest member, Michael Arkk. Devoted fans do not need any introduction. Maybe the members wanted to stick to their musical professional lives, and not their personal lives, but it is a missed opportunity to learn more about them. Later on, they reveal whether they had day jobs or had successful musical careers, stayed in Britain or moved, but there is no sense of who they are as people when they are not playing music whereas some others talk about their glory days and not making money but loving the job. Who are they without an instrument in their hand? Do they have families, hobbies, etc.? If they are the Jamaican music equivalent of The Beatles, everyone has a sense of John Lennon and Paul McCartney off stage, but no one from The Cimarons gets that treatment except with a casual aside about the vocal styles. By the end, they are distinguished in terms of whether they are healthy enough to resume life on the road almost a lifetime after their band went on a hiatus. There could have been a story about why one person left and another took over, but it is skipped over.

“Harder than the Rock” is mostly chronological but offers little context other than providing assertions. It is also indiscernible why Warmington decided to let the years 1967 and 1975, etc. take center stage when the story was soon going to jump to other years. Again, people who are contemporaries with the subject or have a Caribbean or British background will have no problem following, but a movie has to be a bit timeless and welcoming to acolytes. What is Windrush? Most Caribbean or Black diasporic people know, but it is a missed opportunity to inform those hungry for knowledge. If reggae is so different from other forms of Jamaican music like ska, bluebeat and rocksteady, spend more time distinguishing them. What if a viewer has no idea how any of them sounds? Talking heads assert how unique The Cimarons were in comparison to other reggae bands without explaining that difference. Warmington could have shown it. The documentary did a great job of explaining how the Cimarons were session players who did not get credit for playing on famous albums, but showing the records was not as helpful as perhaps playing each one in succession. It is possible that getting the musical rights was too expensive but maybe getting interviews with the singers who worked with them could have been a more affordable option. There is an assumption that people know about punks or Notting Hill Riots without taking the time to root the audience in the overall background story, but kudos for memorializing Eric Clapton’s hypocritical stance on reggae and immigrants.

“Harder than the Rock” is more comfortable in broader concepts without details such as discussing shared oppression through colonialism, and racism/nationalism with the Irish and Jamaicans as Black people, i.e. whom they describe as Africans. People who are fans of Irish music, especially Cian Finn and Christian McClann, aka DJ Bellyman, should check this documentary out because this element occupies a sizable portion of the story. There is an approachable mini-history lesson about The Troubles. It was missed opportunity to not parallel Jamaica’s history of rebellion against occupation with Ireland, and Jamaican history is largely omitted other than the most general idea of enslavement and referencing Paul Bogle while omitting why he is a household name. It is in this segment than reggae is described as “rebel music.”

The second half of “Harder than the Rock” has a narrative which is clear to follow and feels more biographical beats. It chronicles The Cimarons’ relaunch efforts and shows Arkk at home and his day job. He discusses his hopes and dreams. If Warmington had structured his film using Arkk as an unlikely, wide-eyed everyman entry point, the first half would feel less like a live action resume of accomplishments with superb production values and a great soundtrack. Arkk was unfamiliar with The Cimarrons before he became their lead singer, and he could have introduced each current member before segueing to more personal biographies of each member. Then each veteran member could have talked about the people that they miss with a similar detour to offer a little biography. It is so strange to get more of a sense of the newest member as a person than anyone else.

“Harder than the Rock” showcases The Cimarons’ music and will succeed in taking longstanding fans down memory lane lined with metaphorical golden albums. Warmington is too close to the project to make the band, era and music more accessible to viewers without a preexisting connection to the story. If you belong in the latter category and just treat it like a musical sample jukebox with occasional orienting exposition, you should be able to enjoy it. Just have a notepad nearby to jot down anything that interests you and requires more research.