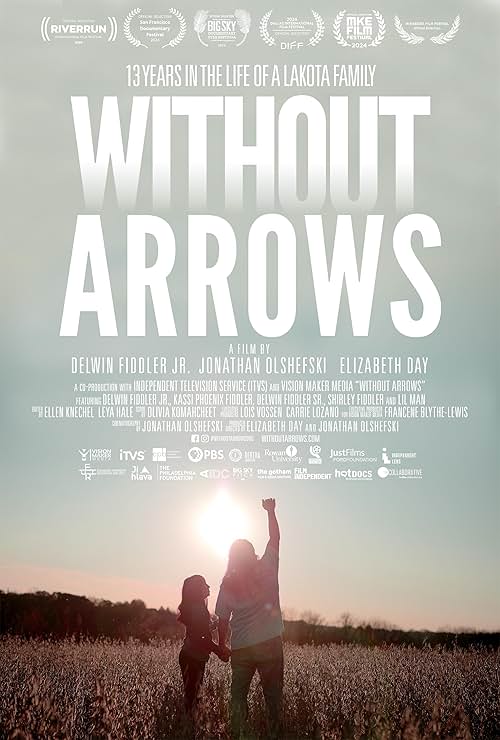

“Without Arrows” (2024) is an observational style documentary which means that there is no narrator to explain what you are watching. The film follows Delwin Fiddler Jr., an enrolled member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, from 2011 to 2022 (the description says that it was filmed over thirteen years) as he lives in two places: his chosen home, Lënape Territory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and his hometown, Green Grass, South Dakota. The biographical documentary uses Delwin as an entry point to examine the life of a Lakota family in twenty-first century America and how they balance preserving their traditions with living in the contemporary world. Through all his journeys and the passage of time, Delwin embraces that challenge and is determined to transmit his knowledge and zeal to others.

Each movie is not made for everyone, yet a film can have inherent value even if the audience will not be broad. With an eighty-five-minute runtime, it shows a slice of life for over a decade and is not structured like a traditional narrative. The closest analogy would be a home video, but it would be too reductive since there are clearly themes revisited throughout the film, and an overall structured story even if the footage is spontaneous. Unlike a home video, first time codirectors Elizabeth Day, who is a first time director in any capacity and a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe tribe, and Jonathan Olshefski, who directed one documentary previously, capture vibrant colors, a visual sense of the intimate and majestic and do not include everything like a home video would. The exterior South Dakota shots are transcendent, and Philadelphia makes civilization pale in comparison. The film follows the Fiddler family over the years with Delwin Jr.’s travels determining the rhythm. “Without Arrows” is the cinema verité equivalent of Richard Linklater’s “Boyhood” (2014) and could be called Manhood.

Delwin starts as a thirty-year old man torn between two homes. In Philadelphia, he expands his knowledge as an indigenous person and is gainfully employed, but he is often depicted as the lone Native in a sea of tourists or non-Native pupils surrounding him, their teacher. In Green Grass, he is part of a loving community and can be a person, not a leader or inspirational figure. He can be nurtured and support others, but life is not easy, and there are fewer job opportunities. His parents try to pass down their knowledge of family history, Lakota religious practices and caring for horses, but even with best efforts and eager listeners, the lessons do not take root for some listeners. No pupil is perfect, but a mistake leads to the accidental strangulation and death of a horse, and sensitive viewers may not recover from the blow. There are other ways that practicing their faith and original lifestyle is not harmonious with available tools. For example, when a pipe is unwrapped, tobacco is supposed to be inserted and smoke blown to spread blessings, but the only available tobacco is cigarette smoke, and the improvisational move carries the dangers of secondhand smoke. Transporting a buffalo is a logistical nightmare if a sedan is the only vehicle available for transport. Apparently Native American audiences resonated with this scene and received it as a relatable, common, comedic experience.

When Delwin is in South Dakota, he steps back and lets his family take the spotlight, especially his mother, Shirley Fiddler, who carries the memory of her birth family, the Elkins, and seems to be the most influential in preserving tradition. She is more talkative than her husband, Delvin Sr., but the couple wear a lot of clothing which suggests that he was a veteran though it was never discussed. Delvin Jr.’s brothers, Derek and Kenny, are just as enthusiastic as Delvin Jr, to practice the old ways. Nephews Francois and Lil Man and nieces Chenoa and Naniyetu also appear onscreen, but Lil Man stands out as the most Westernized member of the family. Even though it did not matter in terms of telling the story, it was unclear which niece and nephew belonged to which brother, and some people appear on screen but are unidentified. Similarly, as the family expands in subsequent years, some people and stories are relegated to remain off-screen though they seem to play a pivotal role. That decision felt abrupt and like a missed opportunity either out of respect for Delvin or an effort to maintain the image of family harmony though it does not whitewash all the family’s travails. The film is just a little too coy as if children spring fully formed from men’s heads with Shirley as the exception.

Preserving Lakota traditions is about saving lives and insuring the Fiddler family’s survival. One off-screen death that predates the filming of “Without Arrows” was a suicide of a close family member, and a strong sense of identity and history saved others that the tragedy touched, including Delvin Jr. This documentary otherwise avoids all the usual tribulations that could be expected to be covered in a film about Native Americans. It is about life not substance and alcohol use disorder or the epidemic of sexual violence directed at indigenous women. Instead, the film documents how Delvin develops into a medicine man in public and a good father to Kassie Phoenix as their play tradition of descending hills, natural and synthetic, evolve, and Delvin’s age reduces his capacity to cavort.

It is also heartbreaking to witness family members’ health and mind deteriorate. Their deaths really hit Delvin hard, but do not kill Delvin’s desire to return home, this time with his daughter in tow. Sunrise and sunset. The pandemic is not explicitly addressed but referenced as people wear masks or are unable to see relatives because of quarantine protocols. The impact on the community, which could have been disproportionate to the national average if they experienced the same medical disparities as other reservation communities, is never addressed.

Apparently, screenings of “Without Arrows” were held in Fiddler homes, and newer members used the movie to connect with people that they never met; thus, making the documentary into a kind of moving picture album, primary document and memorial to preserve family, American and Lakota history. Delvin Jr. pitched the idea for this film to Olshefski, who is not a Native American, who then reached out to Day to ensure equal representation behind the camera as well as in front—talking to you, Matt Damon.

“Without Arrows” is not for everyone. Some will find it challenging to watch a documentary without the guidance of a narrator or professional talking heads offering context to the Fiddler practices as representative or individual. In a day and age when most filmmakers do not have faith that viewers will understand anything unless it is painfully spelled out or simplified, it can result in weakening analytical muscles of even the most experienced open viewer who may find it hard to watch a movie without a conventional narrative structure like sailing without a compass and being unable to navigate using the stars. It is not the kind of film that permits multitasking so unless you are willing to give it your full attention and go with the flow, it would probably be better to wait until the conditions are right, or you feel mature enough to watch it without sounding like a toddler on an all-expense paid trip but tired enroute.