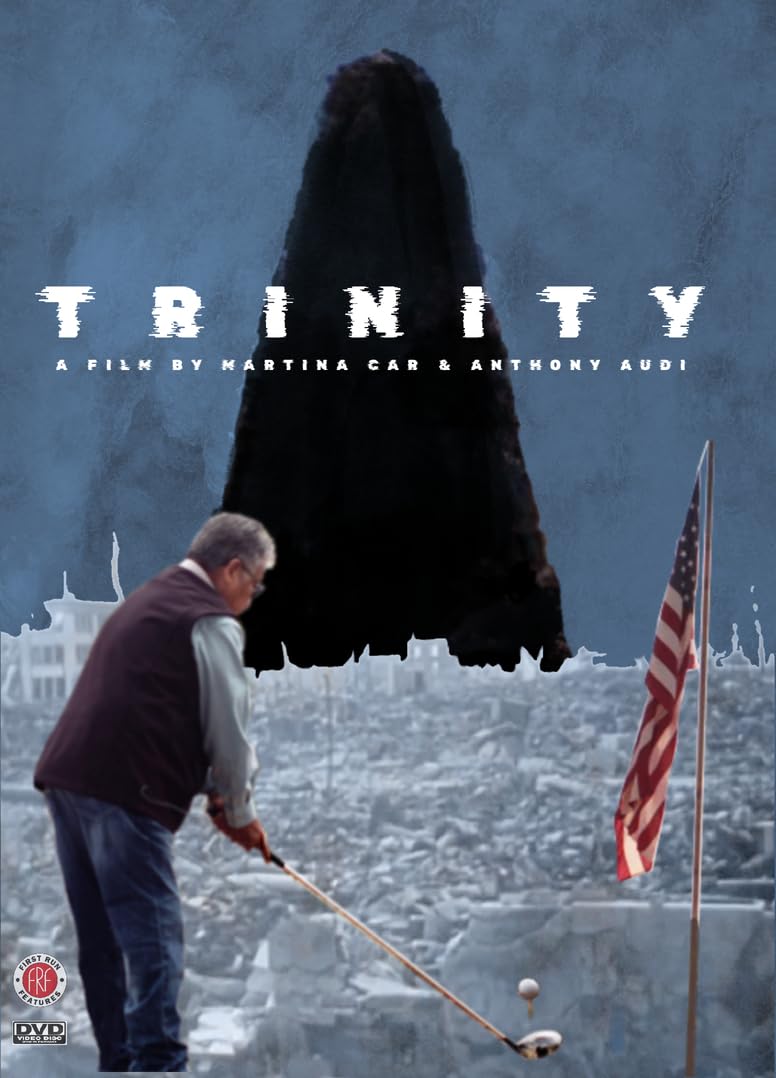

After “Oppenheimer” (2023) came out, critics complained about how the movie praised the titular scientist without showing the deleterious effect of the first nuclear weapons on ordinary people: Native Americans and Japanese people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For people who resonated with that complaint, “Trinity” (2024), a documentary about how the Manhattan Project affected the “downwinders,” i.e. New Mexicans, including the Navajo people. Directors Martina Car and Anthony Audi have good intentions, but their film falls short in telling a powerful account.

Sometimes a story is so innately important that it can transcend a movie’s flaws. “Trinity” is the embodiment of Maggie Kuhn’s quote, “Speak the truth, even if your voice shakes,” and this film wobbles. It is a mix of snippets from black and white archival films about the nuclear bomb and Native American children being sent to boarding schools, excerpts from interviews with affected New Mexicans, news archival footage and home videos. It aims for contrasting comprehensiveness but ends up feeling like a buoy moving with the oceans’ waves with no solid center. When a story is not known well, it is important for it to have more structure, so it does not feel like easily forgotten anecdotes imitating puzzle pieces in a box dumped on a coffee table in need of assembly. The directors need to layout a beginning, middle and end using all the elements instead of hoping that the viewer can put it together even if it is laid out in a more atmospheric fashion.

Phil Harrison, a Navajo man, is the interviewee who comes closest to conveying a cohesive story because he brings a sense of historical scope to his testimony, which the directors correctly latch on to, but fail to recreate with other “Trinity” interviewees. This portion of his interview does not appear until close to the end of the documentary. Harrison starts with the Long Walk of the Navajo, or the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, which is when the US federal government deported and ethnically cleansed the Navajo people. It is first link in a chain of documented times that the US harmed Native Americans, then continues through robbing the Navajo people of their Second Amendment right to bear arms, making it illegal to speak Navajo and separating children from their parents by sending them to boarding schools, which Harrison attended. He does not mention what is now known that those institutions abused and killed those children. It is not until World War II when Navajo speakers were encouraged to use it as part of the war effort while simultaneously civilian Native Americans were unwittingly putting their lives in danger when mining the radioactive materials, uranium and plutonium, that made the bomb possible. Most of those mines were not remediated until the start of the twenty-first century, which means that the runoff poisoned the drinking water. So not only did the fallout from the July 16, 1945 detonation affect the population, but a systemic historic bias enabled that to happen, which then affected the broader population including white people, women, children and veterans.

Instead of “Trinity” telling that story clearly, the ailments and outrage defines its interviewees, which include Louisa Lopez, Bernice and Toby Gutierrez, Laura Greenwood, Mary White, Tina Cordova, Henry Herrera, Bill Payne, Rowena Baca, James Smith, and Allison Cameron, instead of understanding who each individual is before laying out their grievances and treating them as three-dimensional human beings living their lives to get a sense of how the US government disrupted them. Overall, the physical impression that they make, mostly older, affable types with protest signs without the raised voices or aggressive posture, is what makes them stick out, but a good impression does not make for a whole person that an audience can relate to and remember. The overall message is that there was no consent before they are still enduring a physical and psychological toll that they never got compensated for. The filmmakers omit that health care is quite expensive for Americans, so this burden is the kind that has widespread ramifications that keep certain people in poverty. Wealth building is impossible if a person becomes disabled or needs medical assistance from the government.

One protestor notes that their story is not a part of documented, local, state, national or global history, and “Trinity” is trying to remedy that situation. Car and Audi do a decent job of identifying the names of the interviewees but can get slapdash and abandon it at fits and starts. If the closing credits had exchanged places with the opening credits, it would provide at least brief context and act as a primer for all the interviewees and footage that is about to be shown, but as it is currently laid out, it is difficult to keep everyone straight, which means their stories bleed into each other and has no form. History told in chronological order is easier to retell and pass down.

If “Trinity” commits an unforgiveable sin, it is the seemingly long stretches of tourist home video with synthesizer music playing. It as if Panis Cosmatos inspired the music, but not the banal visuals, especially compared to Cosmatos’ arresting, psychedelic and surreal cinematography. Sticking a camera up to a car window is not illuminating or even atmospheric. The fact that the area is quirky feels like a trivial feature to focus on. It is not a documentary about Roswell. Sometimes artistic zeal carries people away and leads to self-indulgence—just read any of my reviews. With a short runtime of seventy-six minutes, it makes it feel like filler, which could have traded places with more details on the interviewees’ life stories.

It was impossible not to notice all the surgical masks that the tourists wore. While it is unnecessary to have a narrator, there is nothing anchoring this film in a specific time other than vaguely the twenty-first century, but future audience members will not know it unless they stick around for the credits. The footage was shot on October 2-7, 2021. Time is an important element because it informs audiences how long it has been that these people have not received any satisfactory governmental response.

At the end of “Trinity,” the filmmakers show archival footage of government officials, including Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff William Leahy, President Eisenhower, Commander of the Pacific Fleet in World War II Chester Nimitz, Director of Strategic Bombing in the Pacific during World War II Curtis Lemay, and Nuremberg Trials Chief US Prosecutor Telford Taylor, admitting that the nuclear bomb did not turn the tide of World War II. This compilation should have opened the film to rev viewers up and primed them to be more open to hear the interviewees’ accounts.

“Trinity” is essentially a human-interest story, and even though it would take a special kind of idiot to deny the scientific fact that exposure to radiation is harmful, this documentary never offers substantiating proof to supplement the stories even a montage of obituaries, medical documentation, etc. There are no talking heads like scientists or medical professionals discussing what they witnessed, but it also could be because the interviewees claim that these people disregard the effect of this exposure on their medical diagnoses.

“Trinity” tells an essential part of history but is not as effective as it needs to be to tip the scales in the survivors’ favor or become required viewing for anyone interested in a complete story after watching “Oppenheimer.” Herrera died before this documentary was released so another filmmaker needs to get out there and see if they can improve on this sincere attempt that falls short of what this subject deserves before any more first-hand witnesses die.