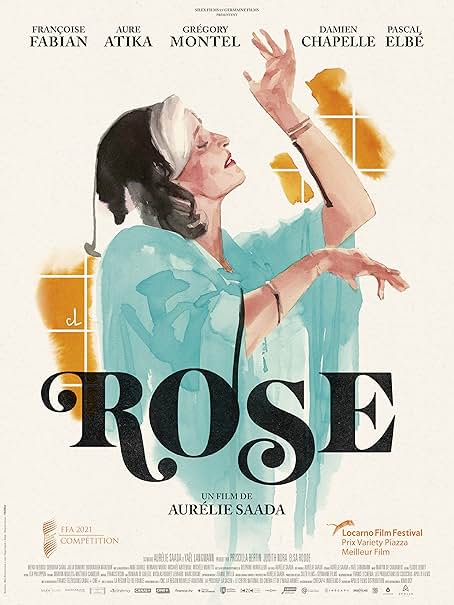

“Rose” (2021) refers to the Tunisian Jewish widow, Rose Goldberg (Françoise Fabian), who is adjusting to the loss of her beloved husband, Philippe (Bernard Murat), and discovers that she is a late bloomer. Better late than never. Her three children, Pierre (Grégory Montel), Sarah (Aure Atika) and Léon (Damien Chapelle), debate about how to help her while navigating the situation as prospective caretakers and fatherless adults. Mourning comes in a lot of forms, and so does life. What will Rose’s life look like? French singer and actor turned director and co-writer Aurélie Saada’s feature film is a relaxed, grounded film about ordinary people facing their mortality and other forms of loss with a determined joie de vivre.

Fabian is a riveting presence and handles the central role with ease transforming from the content, joyous wife to a woman still elegant but fraying with the rupture in her identity and routine and ultimately lands as a woman enjoying a second adolescence. “Rose” nails how socializing with strangers opens pathways to unexplored new identities and experiences. When Sarah takes Rose to a dinner party, Marceline (Michele Moretti), another older woman, demands her participation and laughs at the absurdity of Rose’s identity rooted in a relationship to a dead person. After disassociating and letting the animated waves of conversation wash over her, Rose gets jolted out of the role of chief mourner and unnoticed bystander and back into her body and life. A party game makes her wonder what she wants out of life. Fabian is gorgeous even at her character’s nadir, but unlike actors like Helen Mirren, she is more representative of a woman in that age bracket.

Sarah also begins to see her mother as a person, not just a mother, and Atika silently projects the conflicting emotion of awe and awkwardness at the prospect. Sarah is courageous for letting her mother into her life, which includes going to a friend’s dinner party and smoking a joint in front of her, instead of just acting like a sanitized daughter for Rose’s consumption. It may be the most French aspect of “Rose.” Sarah makes a solid effort to introduce her mom to new routines but eventually resumes living her life and falling into her own patterns of coping with loss and begins to ignore her mom’s bids for attention. Eventually she takes a page from her mom’s playbook and finds her footing. As an artist, specifically a choreographer, Sarah could be the onscreen surrogate for Saada, whose grandmother inspired Rose.

The sons are more one dimensional. Pierre has embraced religion, Orthodox Judaism, to overcome earlier obstacles in life and never gave up the habit, but the crutch is not working as well with the added weight of his father’s life and the trite cliché signs of a midlife crisis. If Chapelle was not hot, Léon would be unbearable. He only gets worse with Philippe’s death and is a baby man still dependent on his mother but acts as if he should be the man of the house. If someone treats you like this, call the police on them.

“Rose” does not depict this transition as smooth and pat. Saada does a brilliant job of revisiting situations to show a new side of a character. Within the opening scenes, there are two celebrations of Philippe’s life, and the tone and occasion are different. The way that Rose traverses her lobby reflects her inner life. The first time, she treats descending four steps like the ascent to the highest peak. Another time, she moves briskly through it with ease. The last time, she is initially defeated then sees an older woman toting a shopping cart, and she rejects this destiny. It is an expected, accepted image, but she chooses a path that has the most potential for embarrassment and adventure, risk and reward. She expands the definition of age-appropriate activities. Her relationship with phones change. Initially she does not answer them so she can hear her husband’s voice on the answering machine. Then she calls her daughter frequently on the landline with requests to go out. By the middle of the movie, she is borrowing a cab driver’s cell phone to check on her family. Soon she does not need a phone to connect with anyone because she is too busy living.

Then there are visits to a nearby café, Café Bellerive, with the proprietor, Laurent (Pascal Elbé), to drink by herself, which is a silent tribute to her absent husband. Eventually she embraces what she desires instead of humoring others. Her new attitude ruffles her adult children’s feathers, and the movie acknowledges that regardless of age, women can scandalize others with their behavior. At the denouement, Rose breaks the fourth wall with her declaration of independence. She asks her children, “Does being so exemplary make you any happier?” Will being appropriate make you a better corpse or offer immortality?

“Rose” is not a perfect movie. Because the French are so good at depicting real-life scenarios, the pacing can reflect it. This is a feature, not a flaw, as the act of shopping for lipstick, making makroudhs or going to the spa are treated like epic adventures. It is preferable to movies that treat death like an explosive event that requires breaking plates or turning it into a joke fest. The quotidian parts of life are what grounds the film in authenticity. Also Rose’s evolving relationship to her reflection is a realistic antidote to “The Substance” (2024). By the end, she is pleased with what she sees, and she does not need Margot Robbie as Barbie to tell her and the audience that she is beautiful. She is alone, but unafraid as she realizes that she does not need a mate to be whole.

It is rare for a film to focus on Sephardic Jewish people’s lives as opposed to Ashkenazi Jewish people, who predominantly immigrated to Europe at an earlier period. Nazis treated Tunisian Jews living in France without any special distinction, but if they remained in Tunisia during World War II, the Nazis could not easily deport and send them to concentration camps though they still experienced anti-Semitism under German occupation. After the creation of Israel as a state, Tunisian Jewish people immigrated more to France if secular. It is unclear when the Goldberg ancestors moved to France, but Ruth is from Tunisia. The absence of any reference to the Holocaust is a stark contrast to most films with Jewish characters. It also explains why Rose eventually reveals her disapproval over Pierre’s “orthodoxy.” While she is observant and embraces her culture, she is secular. The décor and fashion aesthetic and culinary choices reflect the region’s influence as much as her love of singing in Yiddish.

If Americans want a film geared towards an older audience that does not insult its demographic, then they better get comfortable with subtitles otherwise they will get stuck with pablum like “The Leisure Seeker” (2007), “Poms” (2019), and “80 for Brady” (2023). Death is not only about loss, but a second chance to be reborn and explore new identities before the inevitable descent to the grave, which does not require a dirge as a soundtrack. As always, no one makes films about death as deftly as the French, and Saada shows great promise with “Rose.” My dearest wish is that she keeps making movies.

Side note: the continuity editor made a forgivable mistake over which heels Fabian should be wearing in one scene after she has a wild for her night on the town.

POSTSCRIPT THANKS TO NAOMI D. TODER ON APRIL 17, 2025 AT 8:19 PM

“In your review of Rose, starring Francoise Fabian, you note the presence of another older woman named Marceline.

You may not know that Marceline is based on a real person, Marceline Joris Ivens, an author and Holocaust survivor, a woman whose personality and joie de vivre couldn’t be more dissimilar to Fabian’s character.

Google her for more information.”