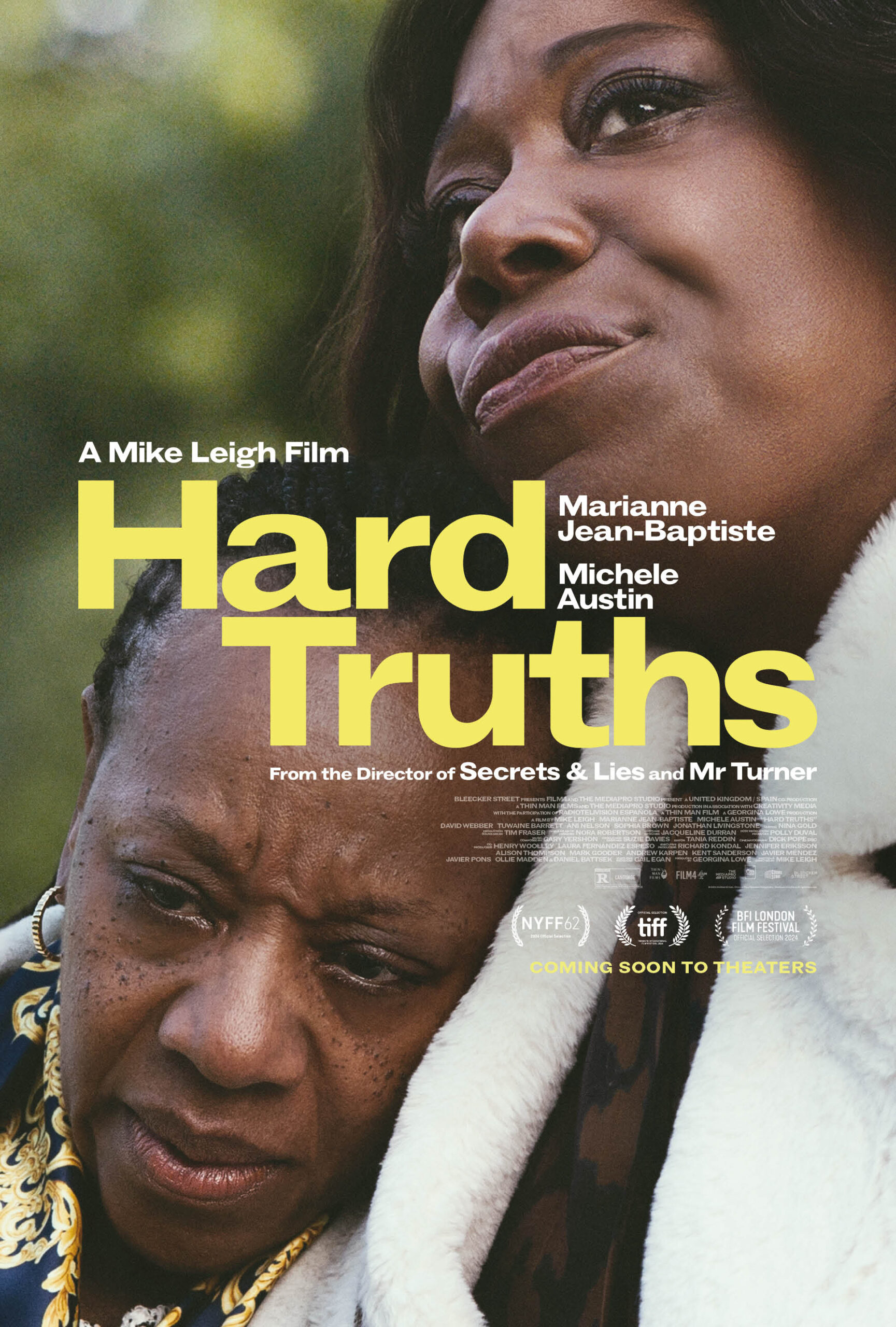

“Hard Truths” (2024) is British director Mike Leigh’s latest film and his second film with Marianne Jean-Baptiste since “Secrets & Lies” (1996). Their collaboration has yielded another masterpiece. This go-around, it is a tale of two sisters that defy any theories about nature versus nurture since the two could not be more dissimilar. Pansy (Jean-Baptiste) is a miserable woman although she is objectively better off than her lively sister, Chantelle (Michelle Austin). Chantelle is determined to have a sister outing to their mother’s grave and invites Pansy over to her flat for a Mother’s Day lunch, but Pansy is a contrary person who opposes everyone and everything. Will Pansy be able to break her pattern?

Jean-Baptiste is a great actor who manages to humanize a truly horrible person without diluting her and making her palatable. Her strength lies in the way that she moves, pauses, projects the inner conflict on her face. Pansy knows that she is her worst enemy, but she cannot stop herself. Sometimes she meets her match. She has negatively impacted her immediate British Caribbean family, the Deacons. Her husband, Curtley (David Webber), the blue-collar provider, owns his own business, CJ Plumbing, has provided a beautiful home and is much more talkative with his coworker, Virgil (Jonathan Livingstone). Their son, Moses Kingsley (Tuwaine Barrett), is a gentle, friendless giant who escapes to his room and on long walks, but grey rocks to make himself the smallest target.

An armchair psychologist would have a field day with Pansy. She is terrified of everything, a hypochondriac, suffers from depression and anxiety, and probably has OCD. Sometimes she has a point, and sometimes her hateful, exaggerated grievances are unintentionally hilarious, especially when she goes on a tear about her quotidian observations about baby and pet outfits. Each person within the same family can have different experiences. She cannot fake waking up with nightmares, but since she is an unreliable narrator, the origin story behind her demeanor is a mystery though parentification, a form of child abuse, and abandonment issues are possible explanations. There are also hints that she was born this way. She derives no pleasure from this mode of existing. If the body keeps score, then Pansy’s complaint about pain may not be in her head.

Leigh, the uncredited grandfather of mumblecore cinema, takes his time developing each character, even the minor ones, and when he shifts to Chantelle, it is hard to tell which character should be centered, her or her latest client (Jo Martin). Her home is colorful, full of light, love and laughter with no judgment as her daughters, attorney Aleisha (Sophia Brown) and marketing analyst Kayla (Ani Nelson), regale her with stories of their latest exploits. Subsequent scenes reveal that her daughters’ circumstances are not as carefree as they appear, but they do not bring their problems home unlike Pansy, who brings her personal hell to the streets and wreaks chaos wherever she goes. On one hand, not allowing microaggressions or professional setbacks to affect their personal lives is fine, but on the other, why do they feel a pressure to fake positivity and not embrace the full spectrum of emotion?

If it was not for the occasional sound of violins underscoring the sadness of a scene, “Hard Truths” would feel like a documentary because the characters, situations and interactions feel so natural. Following someone around all day, especially a disgruntled housewife, sounds boring or like a nightmare, but it is a riveting, compassionate study in humanity. While some of Leigh’s contemporaries like Francis Ford Coppola allow experience and age to permit excess and indulgence in their work, Leigh has not lost a step. The obvious also needs to be stated. Because of Leigh’s filmmaking process where actors play an active role in creating their characters, he accurately depicts people who do not share the same demographic without losing something in translation, stereotyping or whitewashing. His characters are human beings, but he also celebrates the uniqueness of each character. He is not color blind, and it is twenty-five minutes before the first Caucasian character appears on screen, and the diversity does not stop with a mostly Black cast. No Highlander tokenism here: there can be more than one.

The ensemble cast does not feel as if they are acting but appear to be a family. It is a complete contrast to Pedro Almodóvar’s sumptuous, more stylized films where sisterhood and solidarity do not require a blood relationship and tending to graves is an act of celebration. There are two pairs of sisters in this film, and the older pair do not have an effortless relationship, but Chantelle’s bond and empathy keep them together despite their polar personalities. One brief glimpse of a young couple at a furniture store echoes a similar dynamic and makes one wonder how they will fare in the future.

Anger is the easiest of emotions to express, and Pansy lacks the tools to process the others. The way that she applies advice is all wrong. If “Hard Truths” was a more commercial film, Pansy’s resolution would be uplifting or reflect change in the right direction, but in the real world, people do not change overnight and what few tentative steps she takes gets erased as if she took none. It is a heartbreaking reality that even the best efforts are too late and will not be encouraged because the penitent inflicted too much hurt. The grooves in certain neural pathways are too deep. The film begins with a character noting that it is a beautiful day, which it objectively is. The sun shines in every scene. The pigeons coo. It is only later when the story reveals how startling a beautiful day can be to someone.

The camera movement creates symmetrical bookends of the beginning and end suggesting a curiosity over how Curtley and Pansy, who fears flowers for what they hide, will live. They are in a self-made prison of respectability and neither of them is taking any steps to escape or make it work. They do not know how to be together, and they are the one of the few onscreen representation of a man and woman who are together. Chantelle and Pansy only reference their parents’ marriage briefly, Pearl and Carlton. Curtley and Pansy have confused the letter with the spirit of their vows and are together, but apart. In the final scenes, the unseen pivotal act is whether they will be able to depend on each other and finally come together without war or silent disgust. Usually, it is easy to see how others can fix their lives, but this one is a mystery. Curtley does not talk, and Pansy does not stop complaining long enough for anyone to help her or form a connection except Chantelle.

After Leigh stepped out of his comfort zone with two period films, “Mr. Turner” (2014) and “Peterloo” (2018), Leigh is back to making naturalistic, unconventional contemporary films about the ordinary people’s lives in the United Kingdom. “Hard Truths” is the kind of film that defies memory because like any lived experience, it is felt, not a dry prose dump of exposition and explanation.