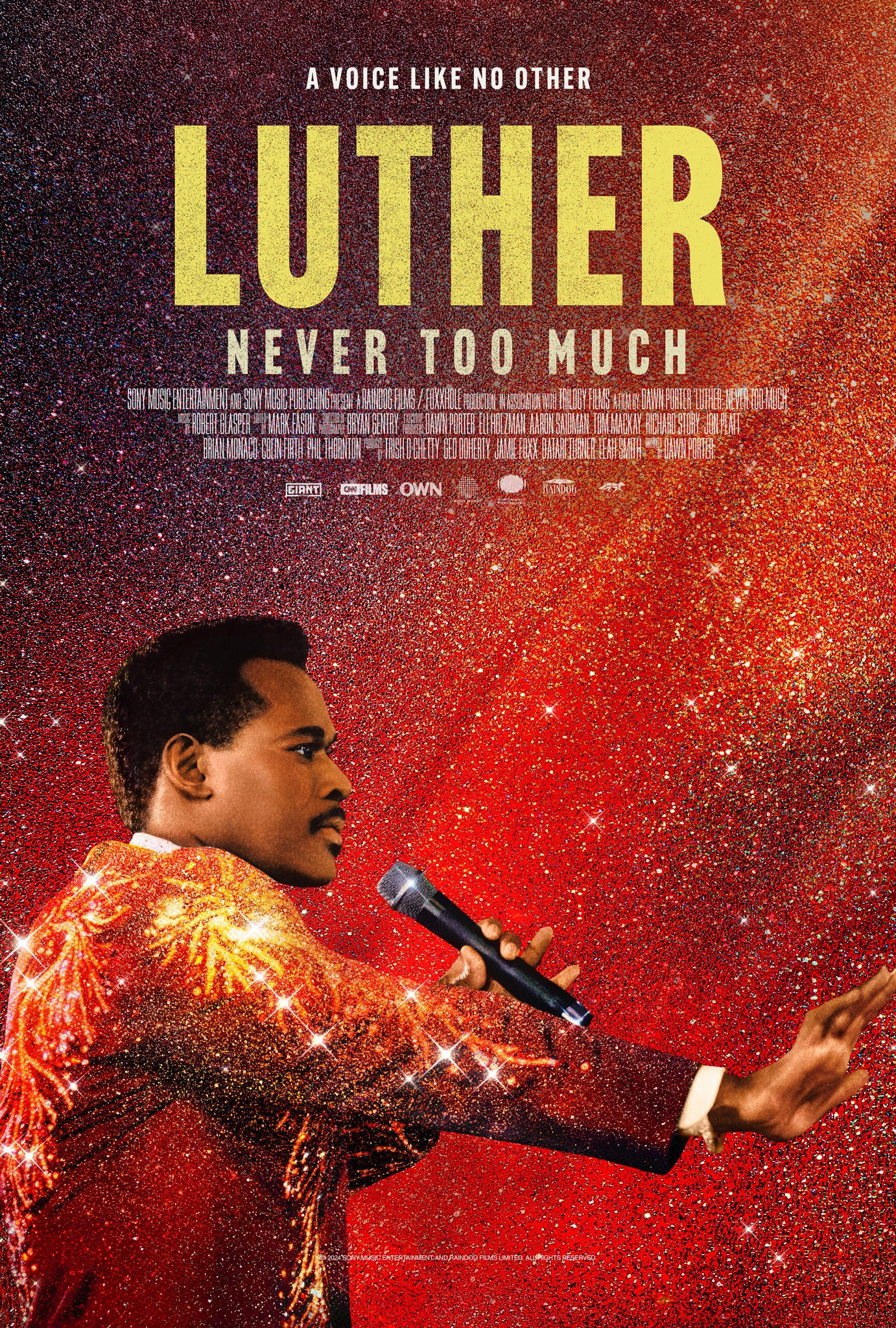

“Luther: Never Too Much” (2024) is a biographical music documentary that chronicles the life of Luther Vandross, the deceased, iconic R&B singer. The subtitle comes from his first album, which was released in 1981. Black American lawyer-turned-director Dawn Porter’s latest documentary—until next month—is a seemingly effortless, entertaining walk down memory lane paved with gold albums. It is a must-see film for any Luther fans, moviegoers who follow Porter’s filmography and documentarians who need an example of how to make a subject accessible to those unfamiliar with the topic while still appealing to those who know all the minutiae.

Porter understands that film is a visual medium. She must have gone through a mountain of archival footage from news and entertainment interviews, concerts, award shows, talk shows, which she then had to edit, to convey to moviegoers, many of whom may not know of the artist, what it was like to exist in the same timeline as Vandross. In addition, she has a gamut of exclusive interviews with family, friends from childhood to adulthood, music collaborators, music journalists, the chairman and CEO of Sony Music Publishing, his former boss Roberta Flack, his idol Dionne Warwick, record producer Clive Davis, icon Mariah Carey, “20 Feet from Stardom” (2013) star Lisa Fischer, and one of the producers, actor Jamie Foxx, who did a skit with the legend on “In Living Color.” In the biggest, unexpected twist, singer and songwriter Richard Marx, who cowrote “Dance with My Father” with Vandross, is Vandross’ anger translator speaking out against racism, fatphobia and friends who divulged Vandross’ private life against his wishes. By juxtaposing Marx’s remarks with a clip of Patti LaBelle giving an interviewing about the subject, the film implies that Marx is throwing shade in her direction without naming names. If LaBelle gave an interview to “Luther: Never Too Much,” it ended up on the cutting room floor along with Alicia Keyes, who appears in a lot of the archived footage with Vandross and at the funeral.

Porter never loses sight of the most important element of the story: music. It is primarily a story of the music in Vandross’ life: his inspirations and idols (Aretha Franklin and Warwick), the sounds that shaped his style (Motown and Philadelphia), the friends whom he bonded with through music, and how music shaped his professional life to become a singer, songwriter, producer and costume designer. If you think that you lived without listening to his music, think again. He is responsible for some of David Bowie’s work, was backup vocals to many notable stars such as Chic and Bette Midler, wrote jingles that will sound familiar to seventies and eighties babies. “Luther: Never Too Much” charts his fame through his proximity to his idols. When he finally gets to work with Aretha and Warwick, it is clearly a huge moment in his life. If you just need an escape, want to sit in a dark theater and listen to great music, this documentary is perfect for you. Even if you do not pay attention to the well-crafted, chronological narrative, you can just listen to the music and pretend that you are watching one of those Time-Life Sounds of the Sixties through Twenty First Century Collection Commercials. If you want to get into his music, this film is the perfect vehicle.

While “Luther: Never Too Much” clearly adores and respects the man, unlike “Piece by Piece” or other music biopics, it does not ignore the controversies that plagued Vandross. It touches on his vehicular manslaughter case, which was dismissed when he pled no contest to reckless driving causing injury, which resulted in a year of informal probation, restitution to the injured and his license suspended for a year. He also settled with the family of his passenger, whom he called his “best friend,” by paying $700,000 and donated concert proceeds to a scholarship fund in the deceased friend’s name. It also devotes a section to his weight fluctuation and speculation over his sexual orientation. Weight was a sore spot for Vandross, especially when he wanted the focus to be about his music. Porter balances the tight rope of not ignoring the obvious while respecting Vandross’ privacy and trying to adhere to the spirit of his responses. Vandross made a conscious choice not to respond to questions about his sexuality. The notoriously diplomatic, affable and marketable Vandross’ final word on the matter was “mind your f**king business,” which was preceded with “what I owe you is my music, my talent, my best effort. That’s all.”

When documentaries are about a contemporary or familiar topic, a lot of filmmakers forget that the film will be viewed in the future when people will not recognize the details. “Luther: Never Too Much” proves that you do not need talking head academics far removed from the subject or tons of narrative stopping exposition to orient moviegoers. Porter occasionally placed the year on screen, but primarily uses montage of newspapers, Billboard charts or interviewees, who are firsthand witnesses, specifying the date, time, place and famous figures.

Aspiring singer-songwriter-producers should watch “Luther: Never Too Much” ready to take notes. Even as a teenager, he performed at the Apollo then “Sesame Street,” which his childhood friend and music collaborator, Carlos Alomar, revealed as being in the cultural heart of Harlem. During the week, he worked his lucrative music day jobs, and on the weekends, he sang backup for Flack. Stamina! Vandross used all his earnings as a backup singer, producer and jingle writer to bet on himself to produce his first album. Despite his indisputable talent, his rise to fame was not easy because he was dark-skinned and overweight. Vandross lived and breathed music with no backup plan, which did not translate into guaranteed success. He had to wait until 1991 to win a Grammy.

“Luther: Never Too Much” is ultimately a sad tale because Vandross died too young at the age of fifty-four after having a stroke and fighting a lifelong battle against diabetes. A lot of the movie features other departed legends like Bowie and Whitney Houston. Whether or not you were a fan before watching, you will leave the documentary wanting to go on a shopping spree and buy his entire catalogue. Well, the biography may be so good that it is easy to miss that it could also function as an infomercial. Vandross’ estate authorized this film and unsurprisingly plans to release a new greatest hits album, “Never Too Much: The Greatest Hits,” on December 13th just in time for a holiday stocking stuffer. Well, played production companies Sony Music Publishing and Sony Music Entertainment. You kept his memory alive, contributed a beautiful documentary to the world of cinema, revived the fandom and recruited a new generation of fans.

“Luther: Never Too Much” is a seamless, conventional musical biographical documentary about a great man whose music still sounds great decades after Vandross died. It is rare for a film to manipulate you out of your money, thank them then hand it over. It will appeal to all ages, and unless you hate music, you will love it. My mom has dementia, and I showed her a clip from the movie. A fellow resident who is usually hostile and screaming just heard me talking about the movie, and she was almost reachable. After she asked to see it, I showed her a clip, and she recognized Roberta Flack. Their home usually does not play soul music, and while both soon lost interest, for a second, there was a connection. Such is the power of Vandross and Porter’s ability to showcase his work without letting her artistry get in the way.