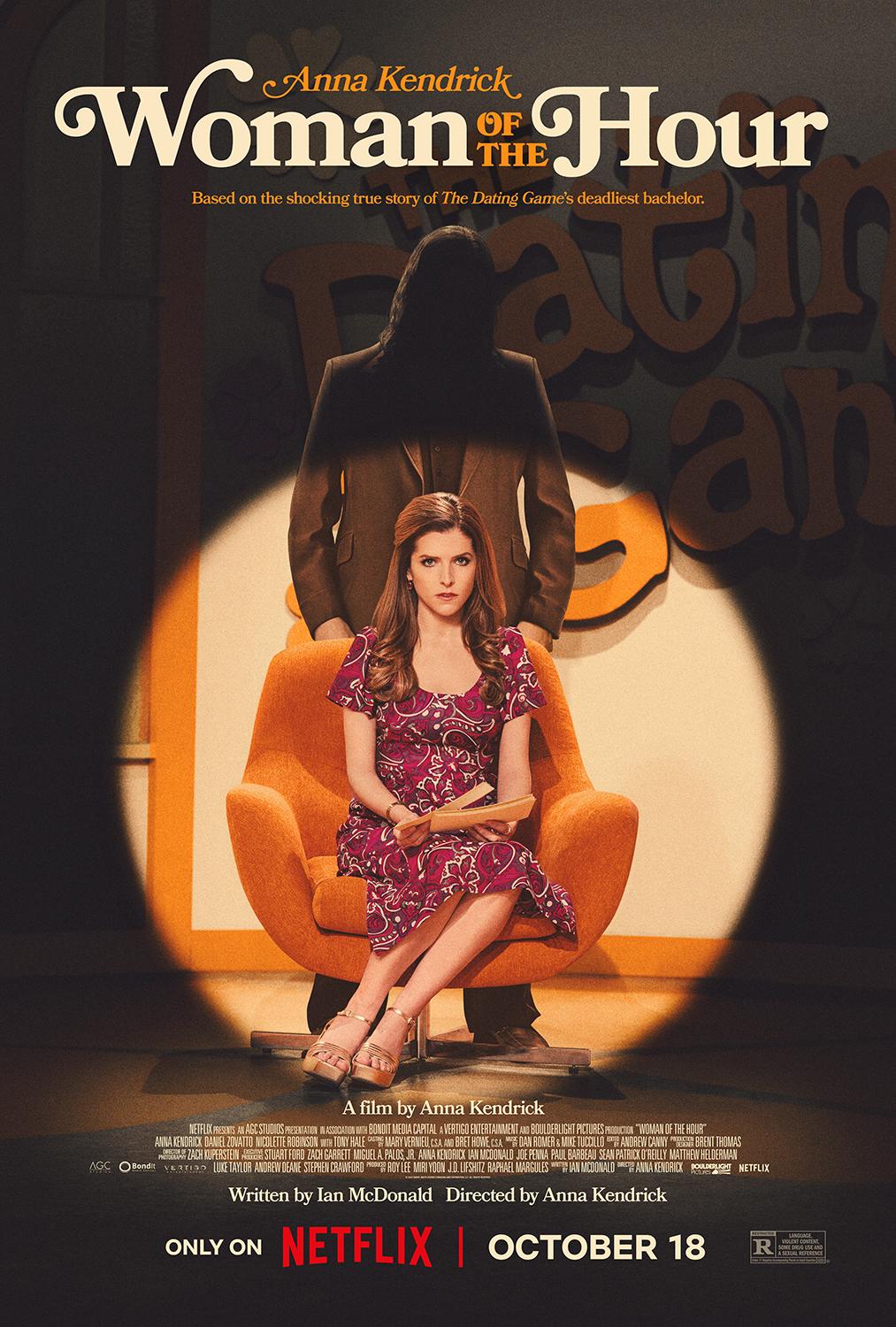

Serial killer Rodney Alcala’s 1978 appearance on ABC’s “The Dating Game” inspired “Woman of the Hour” (2024). On that episode, bachelorette Cheryl Bradshaw chose him out of three men. This film is not a comprehensive study of Alcala’s crimes, but rather poses the question of what kind of society was 1970s America like for a man like Alcala to gain the trust of his targets and not stand out as a predator. Anna Kendrick makes her feature directorial debut and stars as Sheryl, an actor who cannot make it in Los Angeles and goes on the game show for exposure. Rodney Alcala (Daniel Zovatto) seems like a good match when the cameras are rolling., but outside of the glare of the spotlight, he shows another face. It is a fictionalized take on a true crime story that equally praises the girls and women that did and did not get away.

Alcala is not exactly a brand name serial killer like Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer or John Wayne Gacy, which adds to the tension of “Woman of the Hour.” Most viewers will not be familiar with his modus operandi, so the opening is a shock. Zovatto is too good at this role. When police describe a killer as handsome and charming, how many times does the actual person seem incongruous with the description? This Rodney seems safe in comparison to his contemporaries because the bar is in hell, and the average man is depicted as not treating women like human beings. He knows how to listen and talk with women, but just when they let down their guard and deem him as trustworthy, he flips the switch. This movie is less about him than the people who trust him and grow to regret it.

Writer Ian McDonald and Kendrick’s portrait of Sheryl feels anachronistic, but it largely works. She is a woman trying to play the game but is innately allergic to the casual sexism from casting directors, neighbors, and prospective paramours. Because she wants to make it as an actor, she tries to stuff down that side of her by not lashing out at men who objectify her or flinch when men feel entitled to touch her without her permission. Because Kendrick, a successful and affable actor with an edge, plays Sheryl, it is easy to project Kendrick’s talent on to Sheryl and assume that she is as talented as she believes, not a deluded talentless hack. Sheryl’s credibility is key to setting the stage of seeing and judging society through her eyes and rendering the verdict that it is no country for girls or women.

Thanks to the ladies in hair, Gretchen (Karen Holness), and makeup, Marilyn (Denalda Williams), Sheryl becomes emboldened to be herself and just in time, so she does not stifle her natural instincts. As expected, Alcala rises to the top like cream. A warning from the only man who sees something and says something, the lech Bachelor #2, Arnie Aslan (Jedidiah Goodacre), a furniture designer and most unlikely good Samaritan, is insufficient for Sheryl to completely skirt danger. The tension lies in the question whether she will continue to be herself or obey her grooming and become Alcala’s next victim. It does not feel like an accident that after recording the episode, Sheryl resembles Sarah Michelle Gellar’s style from her “Buffy the Vampire” glory days.

During the recording of the episode, an audience member, Laura (Nicolette Robinson) recognizes Alcala as a predator. Laura is a composite of all the people who tried to alert authorities about Alcala. “Woman of the Hour” positions her as a wholesome every woman who is above reproach yet is still not believed. She is not a man hater because she is in a loving relationship. She is a teacher of small children, so she is framed as respectable and honest, yet she is dismissed and embodies the frustration of women trying to save women, and Robinson as a biracial Black actor becomes a microcosm of a familiar futile dynamic.

While watching “Woman of the Hour,” it feels like a quotidian reprise to “Late Night with the Devil” (2024). Lately there have been a ton of movies exploring Seventies television culture. While demons were the guests in the horror film about the pitfalls and danger of unbridled ambition, Kendrick and Donald explore a more human face of evil. Alcala is often posing behind a camera, which recalls alleged indigenous belief that taking someone’s photograph steals their soul. For anyone watching the movie in good faith, there is no confusion that none of these girls or women were willing to do that for fame. Satan is safer in these films because anyone can see him coming, but Alcala is hiding in plain sight. “Seen” versus “looked at” becomes a theme—it is the difference between authenticity and connection versus consumption. Opting out of this gaze is framed as a valid form of protection, not quitting, which is an ironic, damning message for a successful actor to deliver.

“Woman of the Hour” lands a devastating blow on showbiz as a breeding ground for bad men. When Alcala is trying to impress Charlie (Kathryn Gallagher), a recent arrival to New York City, he name drops Roman Polanski as one of his teachers at NYU. In 1977, in the LA Times offices, he shows his photographs, and one of the subjects looks thirteen. Two coworkers debate the suitability of his work, “She’s just 13,” and a woman replies, “Come on. Girls these days…” While the two people are talking about Alcala, it sounds as if it is a reference to Polanski’s conviction for raping a thirteen-year-old girl under the pretense that he would take her photograph and make her famous. Not so fun fact: Polanski has crossed paths and had near misses with two serial killers: a Polish serial killer whom Polanski eluded as a child and the Manson family who killed his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate. This tolerance and acceptability of sexual predation within esteemed institutions create a culture that makes men like Alcala seem normal. It is unfortunate that the film only alludes to Alcala’s alleged male victims.

The narrative is told in a nonlinear narrative. While Sheryl and Laura’s storylines are the anchoring timeline and chronological, “Woman of the Hour” intercuts with notable moments in Alcala’s life from specific targets’ perspective at different times: 1977, 1979, 1971, 1977 and back to 1979. It can be a little confusing and disorienting if the viewer is unfamiliar with Alcala’s crimes, especially since initially, it is understandable to wonder if the film is planning on portraying everyone who falls in that category. The time jumps also do not follow an obvious rhythm. It is impossible to anticipate how long the people who encounter him will be integral to the story, which is unsettling and startling. The sudden flash of violence is a blink and miss it phenomenon that may require rewinding. The good news is that the movie improves with repeat viewings.

“Woman of the Hour” does not devote as much time to Alcala’s targets as Sheryl and Laura, but Kendrick does show life through their eyes. While it takes some adjustment, it is a strong, countercultural addition to the serial killer movie. With its timeless Western isolated landscapes and vast, lonely studio spaces, which feels like a more realistic version of “MaxXxine” (2024), if it was not for the period wardrobe, hair and set, unfortunately it could easily be a contemporary tale.