“The Outrun” (2024) is an autofiction adaptation of Amy Liptrot’s 2016 nonfiction, genre bending book (part memoir, part travelogue, part nature writing) with the same name. After hitting rock bottom, alcoholic Rona (Saoirse Ronan) returns from London to her Scottish birthplace, the Orkney Islands to get sober by working on the farm of her caravan-dwelling father, Andrew (Stephen Dillane, best known for playing Stannis Baratheon on “Game of Thrones”), and living with her devout Christian mother, Annie (Saskia Reeves), but changing locations just forces her to confront the past, not move forward to meet her future. During the winter, she leaves her parents’ island to go to the outskirts on Papa Westray and live in the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) owned Rose Cottage. Will she ever be happy again without drinking?

If the idea of watching another movie about an alcoholic trying to become sober sounds about as exciting as eating boiled vegetables, fear not. Director and cowriter Nora Fingscheidt, cowriter Liptrot and screenstory contributor Daisy Lewis create a nonlinear, lyrical, sensory thematically driven narrative to depict Rona, including her interior, psychological life and track her development from someone disconnected from life to becoming part of it by living fully. Rona’s story does not follow the same traditional beats as most recovery memoirs. Going to rehab and attending AA meetings does not cut it for Rona. Alcohol, a depressant, is only part of Rona’s problem. She implicitly likens herself to a selkie, someone dissatisfied on land. It is really a story about someone trying to find a way to escape the polar legacies that her parents offer her and find her true way independent from another person. Instead of escaping through alcohol or even disassociating through music, she must find meaning in existing and experiencing life as it unfolds around her so when Rona finally embraces and enjoys the most banal existence, eating and laughing to whatever she is playing on her laptop, she has made it—a huge contrast to a film like “A Different Man” (2024).

Fingscheidt and Ronan are terrific collaborators to bring this story to life, but for those moviegoers uncomfortable with somewhat experimental journeys, it could be challenging to follow a story that goes to the beat of its own drummer. To figure out if a scene is in the past (childhood vs London) or present, look at Rona’s hair color or if a child appears on screen. Also are there a lot of people and is the setting more urban and denser? The camera movement indicates Rona’s emotional state: a perfect example of how chaos cinema should be used. To gauge Rona’s relationship with others, look at the framing of the scene as if it was a photograph framed on your wall. In one early scene, Rona is upstairs alone in her shadowy room with the door open, looking down and sedate, dressed to go outside, but a wall separates her from her mother who is only a head and shoulders at the bottom of the stairs looking up with tons of light on her face. The camera often depicts Rona’s point of view, and she looks at people with a broad frame and seeing them through a slit as if she is spying on them. She is usually an outsider staying at the edges of the action, but when she is in the center of it, ask if it feels dreamlike, altered or realistic. More fragmented, counterintuitive close-ups of eyes, fingernails, etc. could indicate interest or intimacy.

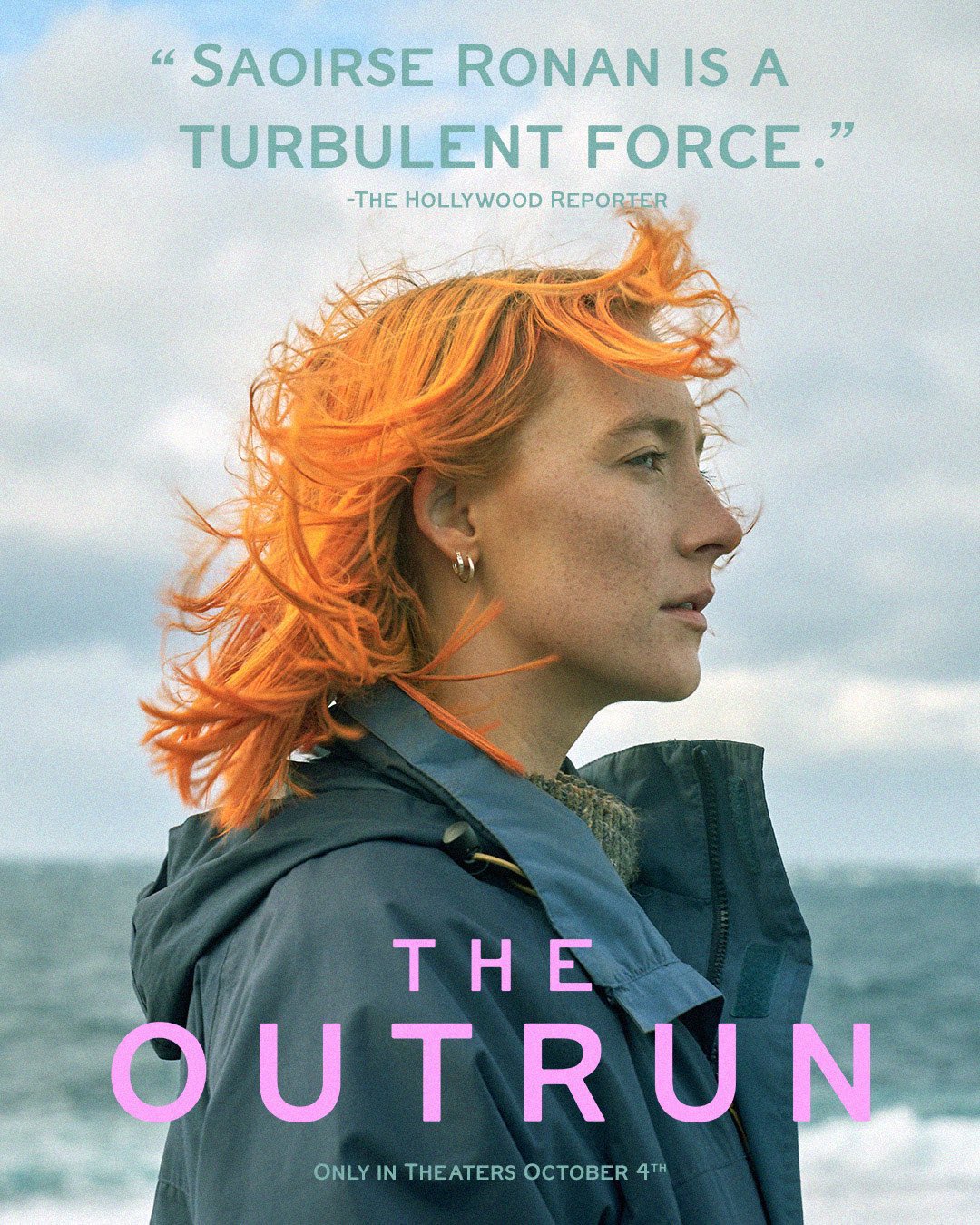

If you are like the youngest brother in “My Old Ass” (2024) and love Ronan, then “The Outrun” is a must see. She stays at the top of her game as a deeply flawed woman. She relates more to her father and feels free to be herself around him. As the story reveals more about the past, Andrew’s delight in his daughter’s return and her mother’s looks of concerns seems less heartwarming and judgmental respectively. As Rona stops idealizing her past, including her relationship with Daynin (Paapa Essiedu), her first true love, she gains the capacity to hold herself accountable and face the unvarnished truth about how she blew up her life. It is also a story about learning how to live well with others whether as a partner, a daughter, a neighbor, a biologist or a steward of life whether domesticated or wild animals.

Mental illness is an essential theme in “The Outrun.” Regardless of whether alcoholism, which is a disease, is also a mental health disorder, Andrew is bipolar, and Rona’s childhood romanticization of his harmful behaviors into fantastic, admirable traits influence her adult conduct. Rona’s unspoken fear is that she believes that she has inherited her dad’s fate and will remain disconnected from human community. What makes this story so countercultural is that it resists the impulse to demonize an action or a history, but makes its benefit depends on Rona’s frame of mind. For instance, one-night stands depend on her engagement with the partner—lack of connection is the problem. Like her father, she loves storms, but it can be done in a destructive or beneficial way. Going to the club and allowing the music and people to sweep you away is only deleterious without communion. Dyed hair and being eccentric can be a sign of a healthy mindset if it reflects a renewed zeal for life. Living in the countryside is not automatically restorative just like living in the city is not inherently damaging. It is a nuanced, balanced story that resists pat formulas on how to live a full life.

“The Outrun” goes off on cinematic tangents with Rona acting as narrator while Fingscheidt gives moviegoers a break from following Rona’s journey and delving into archival footage of the islands’ history as a test site for weapons or illustration of legends as if it is a documentary about the Orkney Islands, which bears the weight of being the lead supporting character. The title refers to coastal farmland that the Atlantic Ocean makes it so windswept, it cannot be cultivated. Without subtitles, it is hard to grasp some of the references to the islands’ lore such as the Mester Stoor Worm, a folklore origin story about the islands. Such meditations run the risk of losing viewers who cannot trace the legend back to its relationship with Rona. The link to Rona is more obvious when she describes the effect of alcohol on those vulnerable to its lure or naturalist illustrations of the elusive corncrakes. Rona is also a biologist so as that side of her is more integrated into her quotidian life, these side notes dissolve into center stage such as Rona participating in a local festival, Papay Gyro Nights, which has pagan origins about monstrous women and signaled the beginning of scream.

Unlike most stories involving pagan folklore or monstrous sexuality of women in isolated areas, “The Outrun” is not a horror like “The Wicker Man.” Even Annie, the Christian woman, encourages Rona to stop placing herself in the role of caretaker and encourages her to make a place for herself in the world independent of her parents and the men in her life. By the end, Rona is comfortable in her skin easily able to traverse the land and sea without losing any ecstasy, her mind or her body. By the end, Rona can enjoy the joyous symphony of nature and manmade delights without losing herself.