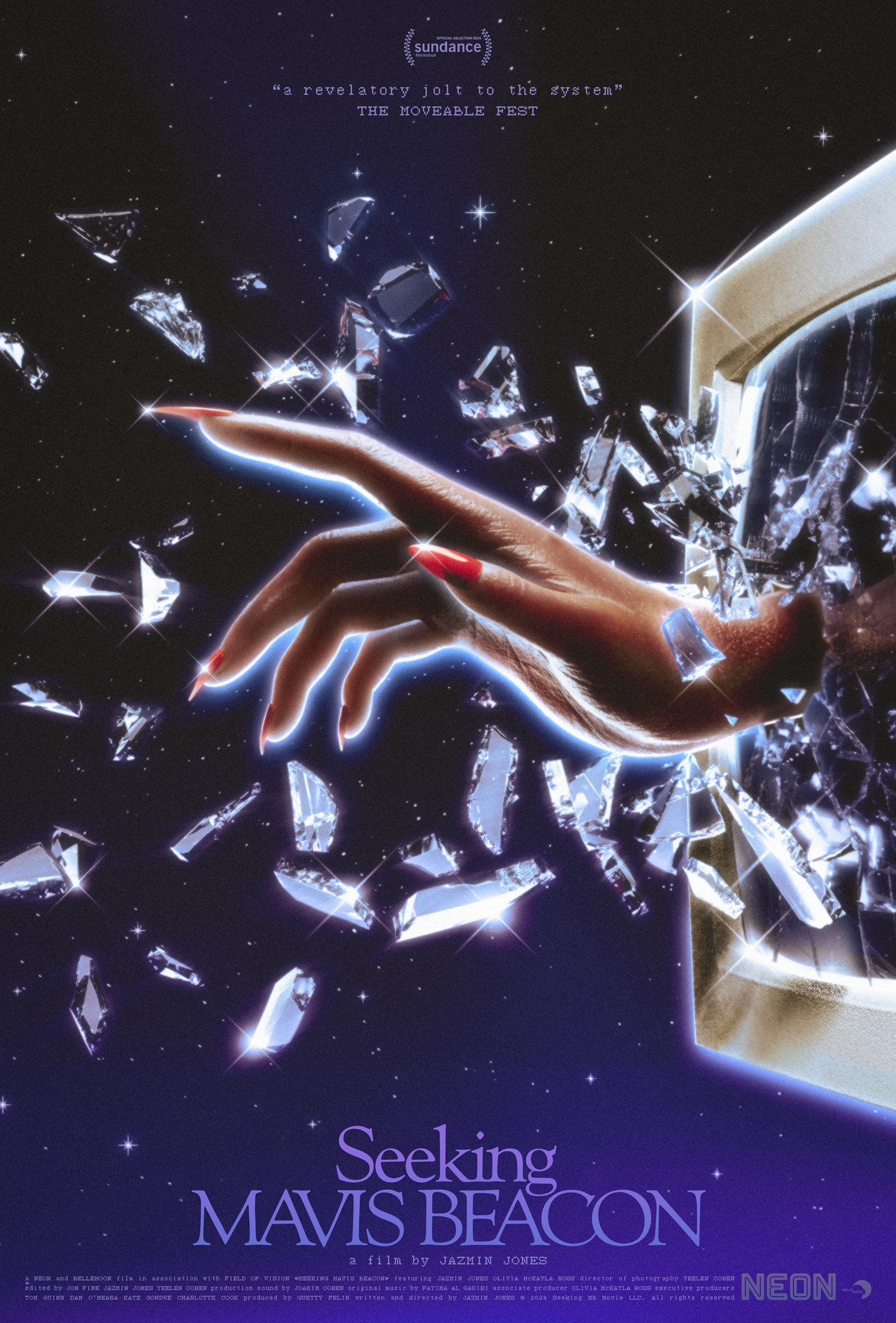

“Seeking Mavis Beacon” (2024) is a documentary about writer and director Jazmin Jones and her collaborator, Olivia McKayla Ross, who was a media darling from Black Girls CODE, investigating the titular woman associated with the software program, “Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing,” which was released in 1987. Their headquarters are in a storage warehouse room in Oakland, California. Mavis Beacon is not a real person, yet she influenced Black people, particularly girls, to embrace technology. Jones and Ross unearth her origin story: who conceived of her, who was the person behind the face on the package, why a fictional person was modeled after a Black woman, and how does this image of race and gender reflect reality or flatten it.

“Seeking Mavis Beacon” is not a traditional documentary, and it should not be. For those unfamiliar with how Mavis Beacon marketing materials, she looks like the expected vision of the respectable professional Black woman: straight hair slicked back into a bun with perfectly styled eyebrows and makeup. In one photo, she is holding a white boy’s hand while smiling despite not looking like a nanny and appearing more suitable for an office.

In contrast, Jones and Ross, huge fans of what this image represented, appear considerably different. They are normal people, but not the kind that usually appear in front of the camera. Their hair is long and as colorful as their clothes and the office’s neon lights. They wear baggy, often casual clothes. Most of the Black women who appear in “Seeking Mavis Beacon” do not fit prevalent media images, which is probably the film’s greatest strength. They more visually resemble the manic dream pixie girl without having to exist to fulfill a romantic partner’s journey towards self-realization. Nerd would not fit as a label though they wax philosophical about technology. Ross styles herself as a cyber doula. Though no one in the film talks about neurotypes, if one or both revealed themselves to be neurodivergent, it would not be shocking news. Jones and Ross reveal the cracks in their production. They get Covid. Ross is a genius who is not getting great grades. Jones maintains her dignity while frustrated that the donated office space gets ransacked then condemned. The film’s tension is whether the people who are supposed to be helping them are secretly rooting for them but are too concerned with their image to just be straightforward.

Jones and Ross begin their search by talking to their family, random people on the street and many talking heads, including Terrell Brooke, a “thought partner,” Mandy Harris Williams, a theorist, conceptual artist and internet/community activist, Stephanie Dinkins, a transmedia artist and AI technologist, and Legacy Russell, curator, media theorist and author of “Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto.” While “Seeking Mavis Beacon” is so rapid paced, vibrant and stimulating, the aggregate visual message is showing, not telling, the audience that there is a wide array of Black women who have the freedom of self-expression with less fear of marginalization and access to opportunity than the woman behind Mavis Beacon.

That woman is Renee L’Esperance, a Haitian model. Jones and Ross are eager to find her, and the software creators, Walt Bilofsky and Joe Abrams, agree to an interview, but are little help in locating L’Esperance. Filmmaker and collaborator test the veracity of thei creators’ account of discovering L’Esperance, but they do not convey why they doubt them and often leave too much time between their interview and their discovery to help the viewer keep the varying storylines straight. Why do they find some stories credible and not others?

“Seeking Mavis Beacon” is at its most provocative when it explores why the software founders decided to use a Black woman as the face of this AI antecedent, a particularly germane question considering this film will be released after “Alien: Romulus” (2024). On one hand, it is undeniable the positive effect that it had on at least the Black people featured in the documentary. It made technology accessible and relatable. On the other hand, Alexa and Siri usually possess women’s voices. The implication is who is seen as a servant versus who is seen as deserving to be served. Here Dinkins discusses her experience with BINA48, Breakthrough Intelligence via Neural Architecture 48*, a robot who looks like a Black woman because it was the creation of a white man, David Hanson, who modeled this robot on his wife, Bina Aspen Rothblatt. Even well-intentioned creators are not immune to problems of accurately representing women or people of color from any other perspective than as an outsider looking in. It is reminiscent of Matt Damon lecturing a contestant from “Project Greenlight” (2015), “When we’re talking about diversity you do it in the casting of the film not in the casting of the show,” and the latter refers to the behind-the-scenes thinkers acting like puppet masters of Black bodies as vessels for their vision. The movie set becomes an unofficial locale for “Get Out” (2017). It would be interesting to know if Jones and Ross considered interviewing Rothblatt, a futurist who hopes to kill death through downloading human consciousness into AI according to her exchange with her synthetic doppelganger in “Bina 48 Meets Bina Rothblatt.” Rothblatt may disagree with their theory.

Still some facts are undeniable. The person responsible in part for the product’s popularity exists in obscurity, and it is unclear whether she was fairly compensated financially. She served the software creators with success as promised while they did not adhere to the contract terms and sought to own their virtual Black face, i.e. have complete autonomy. Unlike most documentaries that will plunge participants into precarious situations without consideration of long-term consequences, Jones and Ross do not allow their excitement to meet L’Esperance or their assumption that anyone would love to receive public adulation to override their critical ethical mind. They do not repeat and perpetuate the founders’ original impact, regardless of intention, of owning and wanting complete control of Black bodies and images, which feels like the technological equivalent of Henrietta Lacks’ cancer cells, theft or slavery. They never conflate the title with seeking Renee L’Esperance. Being a filmmaker can be a profession that lends itself to mental drag more aligned with the demographic of most filmmakers, white and/or male, a concept brilliantly considered in “My First Film” (2024), in which a white woman is confronted with how her image and expectations of being a director contrasts with the reality of a director in a woman’s body during the shoot of her first film. This character tries to adhere to the image of a director without interrogating her assumptions until she is in the thick of it. Jones and Ross do not appear to have a similar dilemma because they never attempt to fit into a paradigm. They are friends first. Their community holds them accountable and provide honest support. They engage in various rituals to locate L’Esperance or to bless their journey. They also interview Shola Von Reinhold, a writer, artist, socialite, archivist and researcher, about her experience as an online figure who has witnessed others inventing her history. Ultimately, they choose to respect L’Esperance’s autonomy and right to decide whether she will participate, which is not an easy or instinctual choice.

Because “Seeking Mavis Beacon” is about experiencing the probe through Jones and Ross’ eyes instead of educating their audience, moviegoers may get lost because there is little to no explanation of what they are showing. If you come to this film with little knowledge of the subject, it will take a while to find your footing. Perhaps Jones and Ross have too much confidence in their audience’s ability to deduce the context and follow their internal narrative logic, which feels as if it toggles between chronological and thematically storytelling but needed a bit more structure and ruthless editing to shorten the run time. It will benefit from repeat viewing, and the screen casting technique of conveying information will give younger people an advantage over their older counterparts, which may have a hard time keeping up with the multitude of images competing on the screen like a barrage of pop-ups. Screen casting is usually a visual narrative technique limited to genres such as horror, sci-fi or thrillers so do not expect a movie that feels like eating boiled vegetables.

“Seeking Mavis Beacon” is a countercultural documentary that many will find challenging if you are going into it blind. If you are willing to go with the flow and give it your complete attention, it will be worth your time, but it is not the kind of film that you watch after a long, hard day. It requires complete concentration, an open mind and a sense of spontaneity.