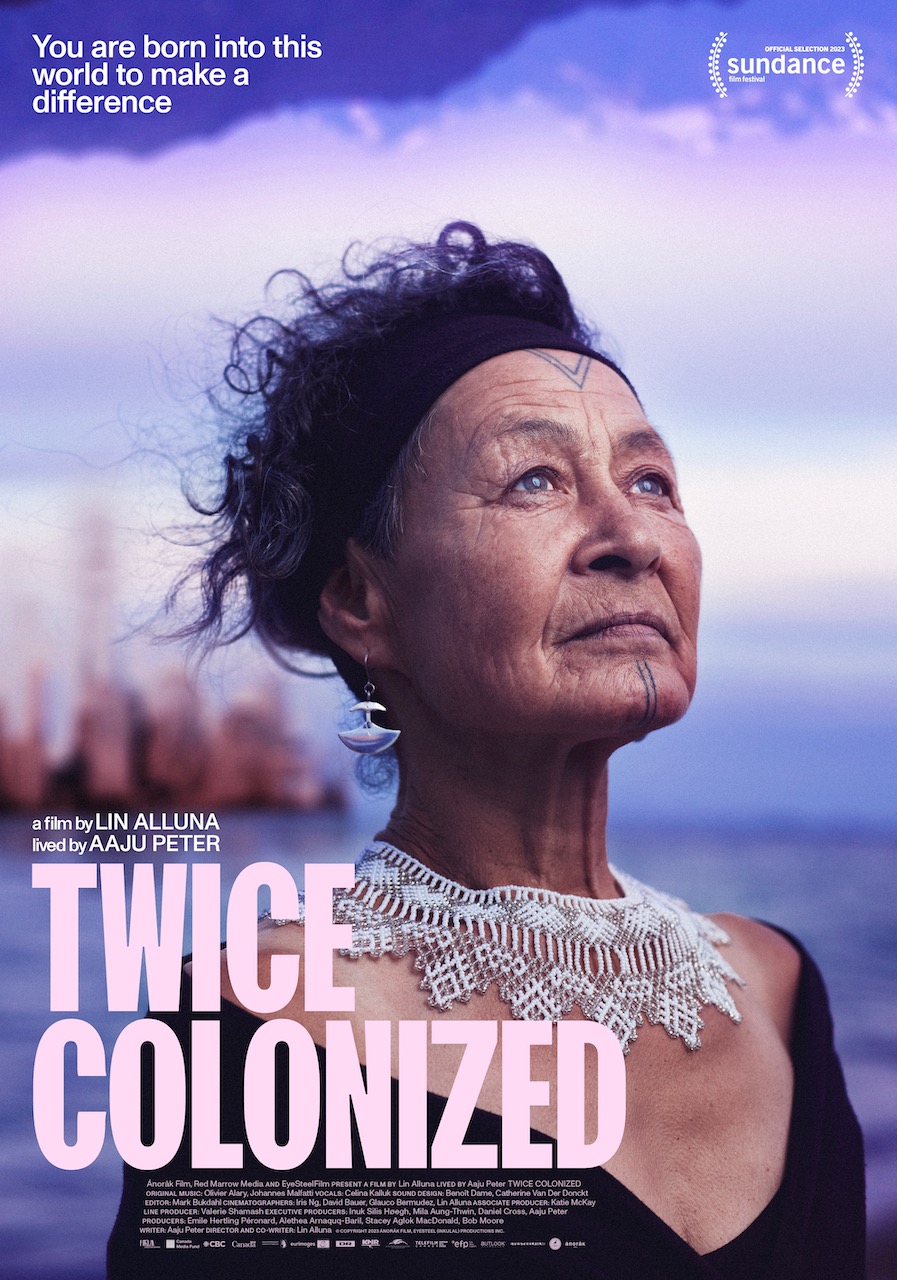

“Twice Colonized” (2023) is Danish director Lin Alluna’s first feature documentary about Aaju Peter, an international, indigenous rights Inuit lawyer who was born in Greenland, educated in Denmark then immigrated to Canada to live with other Inuits under a different system of colonization, thus the title. Filmed over the course of seven years, this ninety-one-minute lyrical film provides a behind the scenes look at the life of this woman. Peter, cowrote this film with Alluna, a white woman and a film student when they met in 2015. Peter chose Alluna to embed with her so Peter could actively collaborate in the filmmaking process.

If one could separate Peter’s reputation and self from the merits of “Twice Colonized,” the reception may be different. “Twice Colonized” is not Peter’s first time in front of the camera. She appeared in other documentary films: “Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattoos” (2011), “Arctic Defenders” (2013), which was about the Inuit creation of Nunavut, which is the Inuktitut word for “our land,” in an attempt to reclaim sovereignty in Canada, and “Angry Inuk” (2016), which defends indigenous people’s right to hunt seals, a cause which Alluna explicitly includes in her film as one of Peter’s causes. Alluna also shows Peter sewing and cutting organic material and displaying her clothes with seal accents but does not note that Peter is also a clothing designer. There is a lot about her life which is omitted that may be included in an average documentary. While Peter may not be a filmmaker, she decided how she wanted to be depicted on screen in a film solely devoted to her.

Alluna and Peter are interested in decolonizing their minds, so it is probable that they made a conscious effort to make “Twice Colonized” into a decolonized documentary. There is no narrator acting as the voice of God. There may be captions to orient the viewer regarding where a scene is located, but there are none indicating whom Peter is talking to or when the footage was recorded unless it arises in the dialogue. One exception is when Peter visits the former Greenland prime minister, who could be mistaken for a close friend based on their body language and surroundings, telling Peter to dump her boyfriend after hearing Peter’s shocking suffering at his hands. It is not exactly decolonizing to name a famous person, but neglect to credit the young activists challenging Denmark’s entitlement by continuing to want to rule over Greenland or the people who help Peter move her stuff from the ex’s place. There is no orienting history lesson other than Peter recounting her experiences. Other than a brief montage early in the film to take us on a rushed, archival news footage tour of Peter receiving awards and speaking at conferences intercut with animal rights protestors, her work is a factor, but not prioritized and never takes center stage. International law is never explained so people will not walk away without an understanding that it is more elusive and theoretical than it sounds. Their priority is to show a living, breathing Inuit woman in the twenty-first century instead of a colonized imagination of an indigenous woman frozen in amber like an extinct dinosaur.

“Twice Colonized” is not a comprehensive autobiography but is impressionistic and three-dimensional in the way that it depicts Peter. Alluna mostly uses original footage that she shot, but it also appears that she uses stock footage about an unknown Inuit girl to illustrate Peter’s account about being sent to Denmark at eleven years old to get an education, which Peter parallels to North American residential schools that were boarding schools for Native American children to assimilate, which is a diplomatic way of not saying genocide—one step is separating parents from children to eliminate culture. Clips from Peter’s home videos also supplement her verbal account of her life story. In her meetings with officials, Peter is outspoken and uncompromising, and even the Danes, whom she calls her colonizers, are deferential, but when she visits the home of one of the Danes who housed her when she was a child, she is much more restrained. Majestic landscapes often appear on screen as an unobstructed, magnified, imaginary perspective from Peter’s POV so Alluna’s camera becomes Peter’s authorized eye.

A lot of “Twice Colonized” shows Peter asleep in bed. It requires a lot of suspension of disbelief that without disturbing her, Alluna positioned the camera over or next to Peter and captured Peter while spontaneously sleeping then waking up. All documentaries are structured and not necessarily spontaneous, but there is nothing harder in a movie, fiction or fact, than to sleep on camera and appear natural even if it was so. All documentarians face the problem of deferring to their subject in exchange for access so explicit collaboration must compound that challenge. If Alluna is like the Danish officials, she probably happily ceded control. Alluna follows Peter as she mourns, goes fishing, washes clothes by hand in her bathtub, listens to loud music, receives calls from her abusive boyfriend, dresses in a youthful fashion and takes care of her grandchildren. A crowd-pleasing scene will be when she dances in her hotel room to a live concert rendition of Tina Turner’s “Proud Mary” playing on her laptop. Many viewers will want to check out when Alluna offers a glimpse of Peter getting dental work.

Instead of chronological order, Alluna shapes the narrative as if Peter was focused, then grief unmoored her. A poetic call through a dream offers her renewed focus to resume her mission to write a book about colonization, which coincides with the midpoint of “Twice Colonized,” a common technique in films to act as a tentpole and gather momentum to the denouement. Beginning with a road trip with Peter and her brother to Greenland, it feels as if the film has settled on a course only to swerve back to Denmark and Sweden to talk with other indigenous people about their personal subjugation during childhood and their current attempts to gain independence and find a place within the European Union, i.e. get a sovereign seat at the table. Peter’s book is not listed on Amazon, so it is probably still in progress unless she decided that the documentary was sufficient, especially since this documentary shares the same title as the referenced future book. In addition, earlier this year, the European Union held a conference and even has an office to act as a pipeline for indigenous people to influence decisionmakers, but indigenous people are not the actual decisionmakers.

Documentaries like “Twice Colonized” briefly allude to the frustration of going hat in hand to people in power, who agree with them but still want to retain sovereignty over them. These films prefer to emphasize the triumph of the individual or the tireless spirit which refuses to be conquered; however, it often feels like a shell game. There is no hesitation about being explicit about past or individual grievances, but there is an implicit fear of alienating contemporary supporters by shining too bright a spotlight on their ongoing sins. It would have been welcome for Peter to confide a knowing wink at the camera that she does not confuse adulation for progress. Do not hate the player. Hate the game.

Coincidentally Alluna and Peter’s joint effort may feel familiar to any potential viewers who also saw “I Am: Celine Dion” (2024). Both films consciously allow the documentary’s subject to be the only expert in her life and be told in her words while the filmmaker follows them as the subject goes about her daily routine. Obviously Dion’s film has more resources at their disposal and slicker production values, but it also feels more substantial. The problem of not offering context in a narrative is that a lot of people are going to miss what Alluna and Peter are trying to convey about colonization. Yes, people will walk away with a better image of one twenty-first century indigenous woman, but there is a lot of talking about doing things rather than showing them being done other than debriefing about when they were done. It is too bad that “Twice Colonized” is not the cinematic adaptation of the book that Peter would write if she had the time. It would require a filmmaker with Ava DuVernay’s talents, more creative control and less in awe of her subject to create a documentary or fictional film like “Origin” (2023) using Peter as the jumping off point to connect the epic story that spans multiple continents and centuries. Alluna and Peter deliver a snapshot, not a thorough biography.