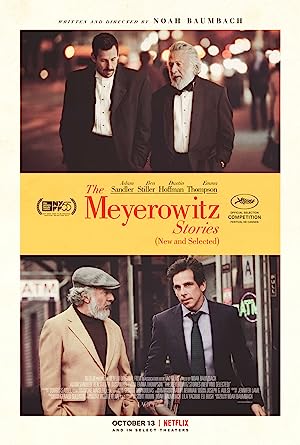

Noah Baumbach was always one of the great American filmmakers, but after his collaborations with Greta Gerwig, he may be improving with age if his latest film, The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), is any indication. I watched it when it premiered on Netflix on October 13, 2017, but waited until this weekend to rewatch and write about it because I knew that it was more than just entertainment. It feels like an unofficial sequel to The Squid and The Whale. The Netflix film focuses on the titular three-generational family at a major crossroads personally and professionally, individually and collectively. Baumbach’s main question is whether or not the family will follow the same dysfunctional track laid out by the center of their orbit, Harold, the grandfather, played by Dustin Hoffman in his last role before it emerged that he is an alleged perv. The majority of the movie follows the men of the second generation, the (half) brothers, Danny and Matthew, with brief moments on their sister, Jean, and the third generation, Tony, who is unseen, and Eliza, Danny’s daughter. The story is chronological and divided by four intertitles, which are reminiscent of wall labels and tags in a gallery and alternate back and forth from individual to group portraits depending on the emotional context of the scene.

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) may be the kind of film that you take for granted on initial viewing because it is a pleasurable movie to watch, funny and organic, but repeated viewings reveal a textured meditation on memory, identity, work, life, communication and relationships. Because the father’s main relationship is with his work, the children’s appreciation or lack thereof for his work acts as a substitute for a relationship with their father. When his children interact with the real world, i.e. the hospital staff, it becomes apparent that most people have lives outside of work and are not as obsessed with it even though their work is literally a matter of life and death. While it is a universal truth that patients and their families are more invested in their caretakers than vice versa, it also signals the pathology of their family. Family life for the Meyerowitz family is work. They try to use work to connect with each other, and the unspoken rule is that the most valuable work is art related.

For me, the most fascinating journey is from individual family units kept separated by the father’s insecurity and neediness to a healthy family independent from the father. The first section focuses on Danny, the older brother, played by Adam Sandler. He emulates his father by valuing art, silently protesting but only hurting himself and exploding in anger. He is unlike his father because he does not want public attention, has a close relationship with his child and is a natural, instinctual caretaker. There is a bonding montage between him and his father, but it is not sustainable. His father sees him as sadly disposable, someone to use, an unpaid companion who should be kept separate from more important people, including his brother, an emotional whipping post when he feels like Danny.

The emblematic scene that explains Harold’s psychological profile is when he is at the MOMA showing for LJ, and he is separated from the curator and LJ initially by distance, then a sculpture then a photographer as the camera shifts from his perspective to LJ. He is literally eclipsed by other’s work and subsequent exposure and fame, which rocks his view of himself and results in him kicking the dog, Danny, to feel better about himself. He seems to think that by distancing himself from Danny, he can distance himself from his doubts and his failures. This visual metaphor is Baumbach at his best. Danny runs towards his father, tries to connect with him by appreciating his father’s work more than the public and promoting it. Harold sees Danny as someone who has never worked and discourages him from taking alimony whereas Danny is the only one who succeeded as a parent and has one good relationship.

The second section focuses on Matthew, played by Ben Stiller in his best comedic dramatic work to date, the only child in the entire movie shown with both his parents. He is the most functional of the Meyerowitz clan in terms of professional and financial success, but he is similar to his father in his early views on Danny, the conflation of his identity with work, his favoring of his flight versus fight instinct, his anger, and his lack of success in relationships. The scene characteristic of this particular father son relationship is when Stiller and Hoffman are finally seated in a restaurant, but are talking at each other about their work and not actually having a conversation. Matthew and Harold are constantly vying for control and favor. Harold literally gives his baggage to Matthew, and Matthew is constantly running away from him unsuccessfully. His father values Matthew’s attention and time.

The third section focuses on all the siblings, Harold’s latest wife, Maureen, played perfectly by Emma Thompson, and Eliza as they adjust to being together without Harold directly affecting the family dynamic. This is the first time that I was ever impressed with Stiller as an actor in the first hospital scene when he becomes a human being and is completely focused and engaged with one person and begins to prioritize family over work. Each sibling has to relate to each other and resolve past conflicts in order to move forward as one unit. Danny realizes, “If he isn’t a good artist, that just means he is a prick.” Is all this dysfunctional damage worth it or a waste? They have to confront the reality of their father, his work and his effect on their family and entertain all the possibilities-the work does not matter and all this pain was for nothing; the work was that good and all this pain was for nothing; and maybe the work mattered and all this pain was for nothing. There is a whole lot of pain, and no easy resolution.

How to deal with pain becomes the central problem of this section? In the first part, Jean is invisible until she chooses to make her presence known then tries to share her work before she is spoken over. Jean finally and briefly takes center stage, which focuses the film in a way that distinguishes it from most films of this type. Baumbach does something with this character that most filmmakers need to do to avoid complaints of lack of representation and for (only) me, addresses a problem posed in Black Panther, how do you unfuck up a situation that you did not start. After Jean tells her story, the brothers make it about them and do something destructive, which seems like a perfect example of appropriation and act as their father would. Jean chastises them, “Unfortunately I’m still fucked up. I could smash every car in this parking lot and burn this hospital down and it wouldn’t unfuck me up. You guys will never understand what it’s like to be me in this family.” The solution is not inflicting more pain, but being yourself irrespective of how the other person treats you. Baumbach tacitly admits that there are some things that he can’t understand or depict, but he can at least admit there is a problem, and that his comprehension of it will always be inadequate.

This solution is not addressed until the fourth section, which reminded me of Columbus, one of my favorite films of 2017 directed by Kogonada. They create a space independent from their father that everyone can be together and enjoy each other. They take turns occupying each other’s space and appreciating each other’s work without needing outside validation. Eliza is key to the creation of that space since she has always maintained contact with everyone in the family. Matthew learns how to get closer to his father and nurture others, and Danny distances himself from his father and does something nice for himself instead of just caring for others. Only the father and Maureen are unchanged by the multiple transitions in a self-imposed exile oblivious to the end of his narcissistic and domineering reign.

The most interesting aspect of The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) is how concepts float around a family, but don’t necessarily take root or reach its intended audience in spite of sharing common ground. You can literally share a life with someone and have no short hand language. I noticed that Harold made Danny wear tuxes to LJ’s show then discusses tuxes with Matthew while watching The Awful Truth. What is the significance of tuxes to Harold and what is he trying to communicate to his sons? To Matthew, it sounds like a non sequitur, but it is germane. His father tells each son separately about an incident with a dog, “You should see the other dog,” which did not initially appear to have any effect but obviously resonated with Matthew who later tries to make that joke to his siblings in the hospital lobby, and it completely fails to land with them even though they heard their father say it before, but perhaps have no memory of it, or they did not hear him. In his last scene with his father, he tries to make that joke with his father, who has moved on to a different act. Danny’s “Myron” song resonates with his father and later with his siblings, but like Matthew, in Danny’s final scene with Harold, he tries to echo a phrase that his father said in the first section without any response. I don’t think that these are minor, forgettable, awkward moments because of one pivotal scene with the only mother in the movie.

Candice Bergen plays Matthew’s mother, and she magnificently delivers a monologue to her son and Harold that is more like an apology to Danny and Jean, who are not present and are never told about this interaction. When Harold tries to extend his uninvited visit or provoke a confrontation, she smoothly ushers him out and lets go of the rope that he is tugging on. I am not familiar with Robert Brault, but I am familiar with his famous phrase, “Life becomes easier when you learn to accept the apology you never got.” That moment later softens Matthew’s perspective on Danny and Jean and makes it possible for him to change in the first section, which in turn creates a space for Danny and Jean to expand and blossom under his newfound concern whereas Harold is a black hole. Harold’s perspective and memories cannot be trusted and are self-serving whereas the siblings may be damaged, but they are not done.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.